Small talk: love it or leave it, but teach it to your TAs

Casual conversation fosters a sense of belonging, but it’s not a universal skill. Sarah Kegley details a short workshop that helps international teaching assistants feel at ease making small talk

You may also like

Popular resources

“I’m so nervous while my students come into the lab before class begins. I have no idea what to say or do.” – Xu, international graduate teaching assistant

If you grew up in the United States, you know that the term “small talk” refers to those mini conversations which take place in unplanned moments, such as while waiting for your class to begin.

But what if you didn’t grow up in the US?

In my work with international graduate students, I am often asked about small talk. While they notice that Americans tend to “talk about the weather” at the beginning of class and meetings, they might not know how to participate. A grad student from Egypt recently asked me: “Should I also talk about the weather before every meeting?”

- Peer review in multilingual classes

- Take care over sharing: guiding student teams on collaboration

- The power of peer to peer: how and why to encourage your students to learn from each other

Many in academia shy away from the idea that such linguistic and cultural knowledge can be explicitly taught, choosing instead to believe that it is absorbed over time. While time is beneficial to processing cultural norms and practices, explicit teaching and coaching of intercultural communication strategy is the more beneficent choice, particularly if we want our students to develop a sense of belonging.

Why does small talk matter?

In terms of pedagogy, small talk serves many purposes, which include fostering a sense of belonging, creating compassion and building rapport among students and colleagues. On top of this, the relationship-building that small talk triggers can be a key to a grad student learning their department’s unwritten rules or even being seen as a team player.

According to biology professor and science education researcher Kimberly Tanner, “if an instructor stands at the front of the room or works on his or her computer while waiting for class to start, students ‘learn’ that the instructor is not interested in students”. Sociolinguists Deborah Tannen and Erhan Aslan remind us that language exposes our identities, which in turn creates hierarchies, barriers, connections and rapport.

But small can be tricky to master and feel at ease using. In fact, many Americans do not enjoy small talk; some will even plan to arrive late at a meeting to avoid having to make it!

At Georgia Tech, almost 40 per cent of our grad teaching assistants (TAs) are international. So, we wondered what could we do, at the institutional level, to untangle this culturally significant speech practice with our international TAs (ITAs), so they not only feel more comfortable in their own labs and classrooms but can also effectively engage at networking events such as conferences?

We now offer a 90-minute workshop/lunch that allows ITAs to explore the purposes of small talk and practise it in a low-stakes setting. The workshop combines background content, research and strategy instruction with engaged, active learning through experience, practice and reflection.

Getting started

Before the workshop begins, we tape printouts of memes and cartoons about small talk on the walls. A Google search for cartoons will provide unlimited content – be sure to filter for appropriateness.

As students arrive and check in, they read these instructions: “Look around at the cartoons/memes about small talk taped to the walls. Choose one that most resonates with you, pull it off the wall, and take it to your table. As other attendees arrive, introduce yourself, then explain why you chose that particular printout.”

We then share research on language and pragmatics to encourage student buy-in and ask them to think about their most recent lab or recitation: what did they do before it began?

I ask students: “How does language usage expose our identities?” They almost always guess: “By revealing our accents.” To that I can add: regional or national accents; vocabulary – what words we use and how we use them; and demonstrating pragmatic understanding.

Using humour to teach small talk

Video is an accessible, low-stakes way to demonstrate what small talk is and its nuances. There are innumerable fun clips on the topic. I like to start with Data – Mr Data, that is – from Star Trek. In this three-minute video clip, Data tries to use small talk. The short scene adds an element of humour to the session. Everyone can agree that his attempt is difficult, weird and awkward.

Introducing rules of small talk

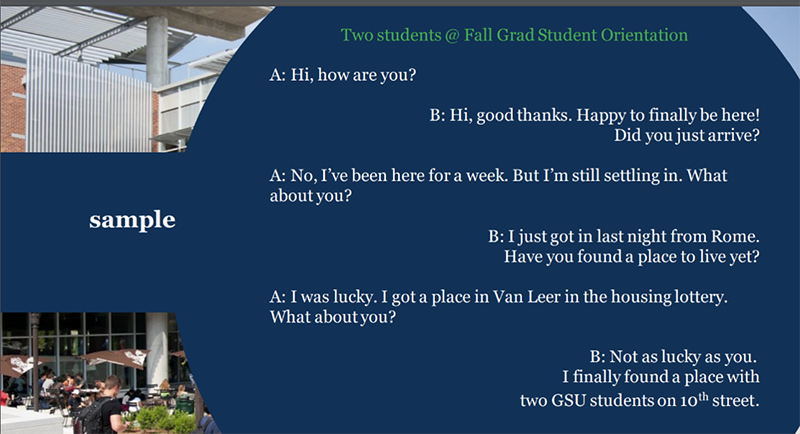

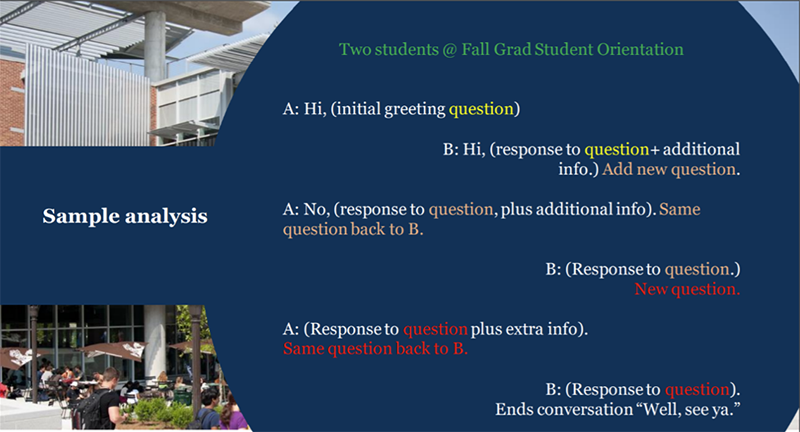

Next, we introduce the rules – yes, small talk has rules. If you’ve grown up with casual chit-chat in English, you may have never realised how fixed the rules are. In the workshop, we share these rules, and an example of a parsed, back-and-forth small talk conversation with the class.

If you need a refresher, here are the rules of small talk:

- Choose simple and uncontroversial topics – safe areas include the weather, sport, traffic, entertainment (such as a recent movie you enjoyed), hobbies and travel.

- Avoid taboo subjects such as religion, politics or health.

- Think of small talk as conversational ping-pong; back and forth is expected.

- Take an interest in others and look for common ground.

- Ask open-ended questions and expand your own responses to yes/no questions.

- Keep the tone positive.

- Avoid dominating the conversation. Three to five sentences for each person can be sufficient.

- Don’t overstay your welcome. Disengage when you sense less interest or a preoccupation with another task.

- Observe body language.

- Remove earphones.

Next, we review a conversation between two students moving into student housing, and analyse the turn-taking process (see below).

Time to practise making small talk

The most valuable part of the workshop is practice, with the goal of gaining confidence using the rules, and automaticity in the ping-pong dynamic of small talk.

The workshop space is divided into settings (corners of the room, or even the hallway); workshop attendees will move from setting to setting for 15 minutes. Each setting has a written description of the context and instructions for the students. As students move from one side of the room to the other, they will choose a role card (A or B). Card A will open and close the small talk conversation. A third card describes the setting and context, and prompts students to use specific topics.

Here’s a sample exercise:

A: You will open and close the small talk conversation.

B: You are standing at the elevator when A arrives. You smile, but do not speak until A speaks to you.

Context: You arrive at the elevators to go to class and a fellow student (person B) is standing there. You will talk about the weather (it was very cold this morning!) and compliment person B’s tennis shoes.

Each student practises in up to five “settings”, and each setting has a former workshop attendee as monitor. We display a large timer on the wall, set to one minute, and students rotate in a round-robin format. After a few practice rounds, we bring in faculty from the Center of Teaching and Learning to add authenticity to the speech acts; faculty stay for about five minutes, engaging up to three workshop participants in small talk.

We return to the large group setting to debrief. Students are asked how they felt during the practice; any questions or comments are addressed. By this time, they are relaxed and, in general, many believe they have improved their skills.

The workshop ends with a final video of blunders in small talk. Late-night talk show hosts often model poor small talk as part of their humour; now that the students know the rules, they can critique what the speakers do wrong. In one case, host David Letterman asks former US president Barak Obama how much he weighs.

Attendees are charged with observing small talk over the coming weeks. They leave the workshop with a handout with tips for turn-taking in small talk, with sample usable language prompts, and they are encouraged to contact me if they would like to consult about something they’ve learned. They are ultimately tasked with initiating small talk with a stranger.

Intercultural competency is strategically constructed

Intercultural competency is something we as educators must help co-construct. Otherwise, we leave the international members of our community to figure out hidden cultural norms and behaviours on their own.

Beyond the workshop, in our classrooms and labs, I encourage professors to help students learn to use small talk practice to their advantage through:

- modelling the use of small talk

- choosing lower-risk topics

- transitioning to the main topic without delay

- not forcing more small talk than is necessary.

Helping our TAs use small talk places a dynamic tool in their sociolinguistic toolbox. This tool adds confidence to their intercultural interactions, which adds confidence and ease to their teaching personas. It’s a win-win, making teaching spaces more congenial, collaborative and effective.

Sarah Kegley is international teaching assistant programme manager in the Center for Teaching and Learning at Georgia Institute of Technology.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

Comments (0)

or in order to add a comment