The trials of teaching a ‘new’ script in a virtual world

Teaching non-Roman scripts online throws up great challenges, but we must preserve the world’s linguistic resources, say Rana Raddawi, Jingjing Ji and Ronit Alexander

You may also like

Popular resources

Imagine you’re 18 years old and you’re just beginning to learn how to read and write in a language you’ve never heard or spoken before. Not only that, but you have to learn it remotely, sitting online in front of a machine with a keyboard that, most likely, doesn’t have the letters of the language you’re about to learn. You’d be forgiven for asking yourself why you’re learning this language. And why you’re learning these strange-looking scripts.

This is likely the current situation of many students who are willing to learn a non-Roman language with a completely different script and great heritage, such as Arabic, Chinese or Hebrew.

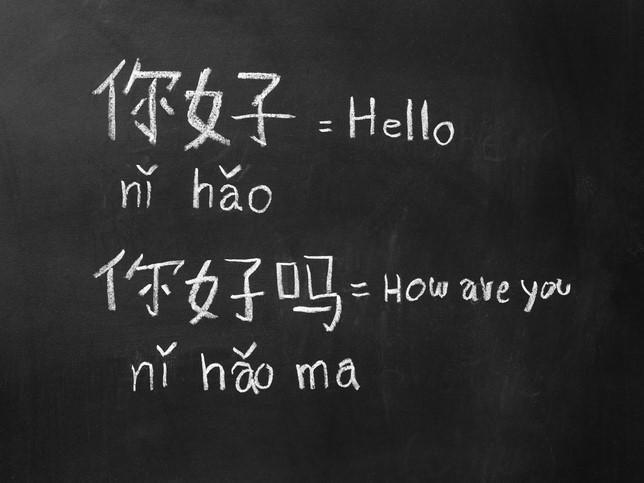

But there are many other challenges that will arise during the learning process, particularly when doing so online. First, students face scripts that are inherently different from Roman languages. In the case of Arabic and Hebrew, students have to write from right to left. Written Chinese, as a logo syllabic script, contains different components and needs to follow certain stroke orders to write each character appropriately.

When choosing a tech tool to incorporate in a language classroom, teachers need to examine the tool closely because many technological tools are Roman-languages oriented. Not every tool will enable typing in different scripts, typing from right to left or recognising refined aspects of the language, such as the strokes of Chinese characters. Often, tools that work well in other online classes cannot be used in language classes that use non-Roman letters purely for technical reasons: the lack of spaces between Chinese characters can make certain tools non-functional in calculating words; a lack of appropriate fonts available for non-Roman scripts; and scrambled words in Arabic.

Another challenge comes with the preliminary teaching of the script. When teaching in person, instructors can easily show students exactly where the letter starts and where it ends. In the classroom, we can be precise, noticing every subtle stroke of pen on paper. Additionally, in the classroom, the native speaker can more easily show the language learner how to pronounce the new sounds that the script carries with it. When teaching script remotely, this becomes more challenging.

This means instructors now face new questions: should my novice student type? Should I teach them how to type, instead of devoting my full attention to handwriting? Perhaps the ideal would be to teach both, knowing the significance of handwriting for these non-Roman languages where, for example in Arabic, letters connect to one another and are usually written differently according to their position in the word. When typing, however, the computer automatically connects the letters for the learner. In Chinese, the subtle variety of strokes can make a difference. Hebrew even has two sets of written language: “block” (which is typed) and handwritten script, which is rarely found on keyboards.

Luckily, deploying advanced tools such as an iPad, wizer.me, Jamboard, Quizlet, Kahoot and more have been very effective and helpful. This year, professors would have been able to plug an iPad into their screens to demonstrate the directionality of each letter as well as the number of lines, and with the electronic pen, we were able to replicate the movement of the pen on paper. Students were also able to write manually with their digital pens or fingers to interact with, annotate and produce writing.

Languages such as Chinese, Arabic and Hebrew are archaic − and that is part of their magic. Learning the script of an ancient language invites learners, from the beginning, to partake in a conversation that is centuries old.

Believers of Islam and Judaism pray with prayer books written in these ancient scripts, the same ones that are used by native speakers for handwritten grocery lists or love letters. Nonetheless, some people might still wonder why they should learn these archaic scripts at all if they can simply speak to communicate.

But the scripts are not just religion and emotion, they are also cultural. Even in the US, truly ethnic restaurants and markets will offer the best dishes and produce in the “secret” script of native speakers. Knowing how to read and write is the gateway to cultural life, to heritage and identity, and even to work opportunities. In the global village of today’s world, being able to use another language to text or write an email is a unique and desirable skill across work sectors.

Language professors had to work especially hard this past year, adapting their methods in order to accommodate the available technology when teaching scripts that are thousands of years old. Some might say they were successful. But this success is crowned by the personal efforts of the students, who devoted time and attention to a uniquely difficult learning process. Perhaps you should try to learn a new script yourself and feel the power of life in another language.

Rana Raddawi is a lecturer in the Arabic language in the MENA languages programme at Northwestern University in Illinois, US.

Jingjing Ji is an assistant professor of instruction in the Chinese language programme in the department of Asian languages and cultures at Northwestern University.

Ronit Alexander is a lecturer in the Hebrew language in the MENA languages programme and Jewish and Israel studies at Northwestern University.

Comments (0)

or in order to add a comment