One of life’s greater truisms is to “be careful what you wish for in case you get it”. The current flurry of activity around the relationship between universities and schools is a case in point.

Last month, the UK prime minister, Theresa May, announced that “universities should actively strengthen…school attainment – by sponsoring a state school or setting up a new free school” to warrant their higher tuition fees. In response, a prominent Russell Group vice-chancellor stated on BBC Radio 4: “We have no experience running schools.” Louise Richardson, the head of the University of Oxford, continued: “So I think it would be a distraction.”

Then, the Higher Education Funding Council for England (Hefce) issued a review of the existing models of such relationships. It is perhaps timely to step back and take a slightly longer view at the higher education sector’s success at increasing access to its institutions, and where running a school might fit.

In 1999, Tony Blair, who was then prime minister, announced the aim of having 50 per cent of people under 30 engaged in higher education in some form. Achieving this required many more young people from disadvantaged backgrounds to go to university.

Over the next decade, universities got many of the incentives that they had been requesting for working on this aim, in particular the removal of the student number cap and earmarked funding. In return, universities delivered an enormous number of outreach programmes focused primarily on raising the awareness and aspirations of the target students.

However, raising aspirations has little direct impact on pupils getting the grades they need to fulfil them.

Although more disadvantaged young people than ever before are progressing to higher education, not enough progress has been made. For instance, entry rates of young people from the lowest participation communities have not yet reached 4 per cent at high-tariff institutions.

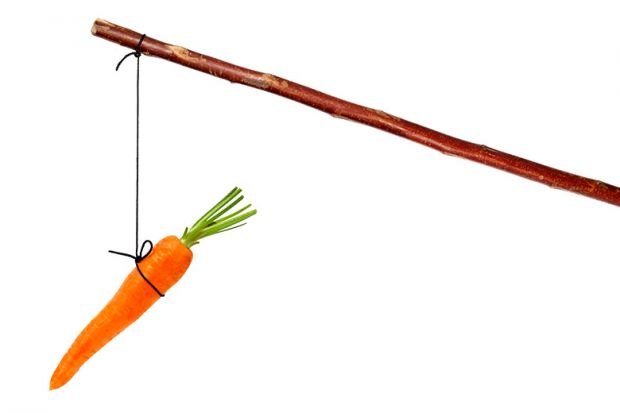

Given that neither the (presumably) widely shared sense of social responsibility nor the financial benefits received have driven enough change, it should not be a big surprise that the UK government has introduced carrots and sticks into the regulatory regime. We got our wish, but we have not gone far enough, fast enough.

I do not agree with the Oxford v-c’s view that higher education taking an active role in secondary and primary education is a “distraction”. I played a leading part in the creation of the University of Birmingham (Free) School, and it is one of the things of which I am most proud – and which got most support from colleagues – in my career in HE to date. However, the government should focus on the ends, not the means, to achieving wider participation in higher education.

It may be that for some universities it is appropriate that they open their own schools or sponsor academies to transform pupil performance. But the bigger impact may come through outreach activities to support attainment in schools, a key recommendation from the recent final report of the Universities UK Social Mobility Advisory Group.

At Nottingham Trent University, we have shown that this broader scale intervention can be successful. In their summer 2014 GCSE exams, 61 per cent of 1,129 pupils with whom Nottingham Trent had engaged over a number of years achieved five or more A*-C grades, compared with 45 per cent of all pupils in Nottingham schools. In addition to the participants’ absolute Key Stage 4 attainment rates being higher than average, their value-added scores were significantly higher, too.

When these students come to study with us, they are also more likely to stay. If they undertake a sandwich year as part of their degree, almost 90 per cent of our poorest students get a graduate-level job, the same percentage as our richest students.

I would argue that the government’s Green Paper, Schools that Work for Everyone, is therefore wrong to state: “universities currently have little…direct control over the factor that has the greatest impact on access – namely, school-level attainment”. If this is so, it is because we have not championed what we can do and have done here.

It is not too late to rectify this. The Green Paper consultation asks if there are other ways in which universities can raise attainment beyond running schools. Clearly there are.

Edward Peck is vice-chancellor of Nottingham Trent University.

Write for our blog platform

If you are interested in blogging for us, please email chris.parr@tesglobal.com

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Oxford’s v-c is wrong: running schools is not ‘a distraction’ for universities

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?