Walking into the Humboldt University of Berlin, statues and even staircases tell a story about the intellectual heritage of Germany’s universities, and the nation’s modern history.

At the gates of the main building – originally a Prussian prince’s palace – are statues of the philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt and his naturalist brother Alexander. As the Prussian government official responsible for education, Wilhelm’s ideas on the unity of teaching and research were key to the institution’s foundation in 1810, and to the development of modern universities internationally. The University of Berlin was renamed in the brothers’ honour in 1949.

In the paving in front of the statues are stolpersteine – the cobblestone-sized monuments to victims of Nazism that are found across Germany and other nations. At Humboldt, they bear the names of Jewish students murdered in the Holocaust, many after being expelled by the university.

Inside, pictures of Humboldt’s 29 Nobel prizewinners, including Albert Einstein, flank the red marble staircase. But perhaps the most eye-catching architectural feature is the well-known quote from Karl Marx – an alumnus of the institution – emblazoned on the wall above the staircase in large gold lettering. Translated into English, it reads: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.”

The quote was put there in 1953 by order of the communist rulers of the German Democratic Republic, who saw Humboldt as the jewel in East Germany’s academic crown. Its removal was debated after German reunification in 1990, but Humboldt eventually hit on a compromise. An artist designed plaques to be fixed to every stair leading up to the quote, bearing the phrase “Vorsicht Stufe” – “watch your step”.

However controversial Marx may have been after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the fact is that egalitarianism has been the watchword of much of German higher education policy in the west of Germany as well as the east. Tuition has generally been free, admission relatively non-selective and all universities funded equally. Hence, it was seen as a big break from tradition when, in 2006, Germany launched a multibillion-euro Excellence Initiative, aimed in part at propelling a handful of German universities into the global research elite (see 'In search of excellence: how the initiative operates' box, below). Humboldt was one of 11 universities selected for institutional funding in the second phase, which began in 2012 and is currently due to end next year.

According to Cornelia Quennet-Thielen, state secretary in Germany’s Federal Ministry of Education and Research, the point was that “if you want to compete in the research world, you have to have some top universities that play in the first league”.

The introduction of the initiative, which has been allocated €4.6 billion (£3.6 billion) of public funding since 2006, came just a year after Germany’s constitutional court overturned a 1976 law prohibiting the introduction of tuition fees. This paved the way for annual charges of up to €1,000 to be introduced by seven of Germany’s 16 Länder, or states, which are principally responsible for higher education. By 2014, political pressure had famously led to all fees being abolished again – just as the first cohort of English undergraduates to pay £9,000 fees were embarking on their final year. But the Excellence Initiative continues. The federal government – which currently provides three-quarters of the budget – has already committed to funding a third round. And while some continue to argue that it is incompatible with Germany’s egalitarian educational philosophy, others insist that it is all the more necessary in an internationally competitive era to create “differentiation” between universities in research.

For the most part, the Länder compensated the universities for the income lost when fees were abolished. But where fees were never levied, as in Berlin, compensation was never paid. Jan-Hendrik Olbertz, Humboldt’s president, tells Times Higher Education that “most” German universities are “underfunded in a very, very serious way…Your own education is such a good investment and you will have a high return from it. For me, sometimes it’s hard to understand why others have to pay for this. But these arguments are not strong enough to convince politicians,” he says.

Olbertz experienced the political wrangling over fees first-hand as education minister in the Land of Saxony-Anhalt between 2002 and 2010, where a plan to introduce fees derailed when centre-Left opponents of fees joined the governing coalition. But in his view, the issue will return to the political agenda because he does “not see other possibilities to get enough money for being successful at an international level”.

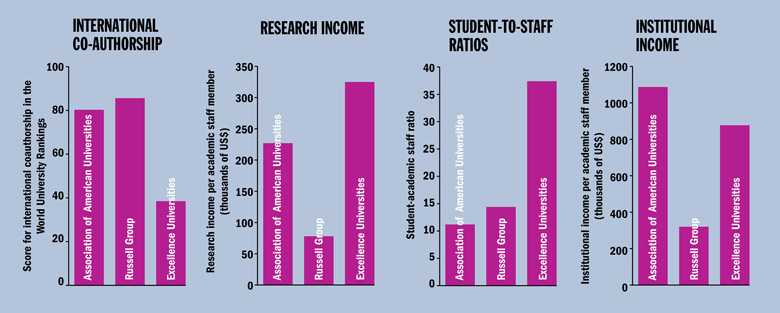

International co-authorship, research income, student-to-staff ratios and institutional income

Note: All data are from the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2015-16

What about those, such as US presidential nomination candidate Bernie Sanders, who cite Germany’s publicly funded higher education system as a role model for a more accessible, non-marketised sector? “In a way…these arguments are right,” Olbertz agrees. “But, on the other hand, I’m not sure we are a role model in quality.” The answer lies in finding a balance “between the aim of quality and the aim of social justice and democratic access to the university”, he adds.

Horst Hippler, president of the German Rectors’ Conference, argues that equality of opportunity for the poorest is “created in kindergarten [and] primary school” – making those educational levels the priority for public funding. As for universities, a graduate contribution, funded by income-contingent loans, “will come. It must come.” But the timescale “depends on how the financial needs of the states are developing”, he adds. Germany is currently “so rich and the economy is running so well [that] I think there is no big pressure to introduce tuition fees at the moment”.

Barbara Kehm, professor of leadership and international strategic development in higher education at the University of Glasgow and former chair of the German Society for Higher Education Research, says that most German university presidents previously backed tuition fees because they saw them as additional income. However, those politicians who supported fees did so because they saw it as a way to reduce public spending on universities. The contradiction between these visions helped to ensure that fees never took off as a concept, she says.

But is it really true that German universities are underfunded by international standards? “Universities in the UK are very much dependent on the amount of money they generate from international students and third-party funding – if they are not successful in that they are underfunded as well,” Kehm notes. German universities “just find their money in a different way”: namely, from the government.

Across the UK as a whole, total per-student spending in tertiary education from public and private sources ($24,338 [£16,893]) is higher than Germany’s ($17,157), according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Education at a Glance 2015 report – the first that includes data from England’s £9,000 fees system. However, Germany is above the OECD average of $15,028. And when it comes to the 11 universities funded by the Excellence Initiative – sometimes known as Excellence Universities – the picture looks even rosier. Data gathered by THE for its World University Rankings (see graphs) suggest that the Excellence Universities outperform the UK’s Russell Group on research and institutional income per academic staff member.

Sandro Philippi is an executive committee member at the FZS, the national union of student associations in Germany, which represents more than a million students. “Students’ unions think it’s a matter of equality and social justice that there are no tuition fees,” he says, adding that student protests were the “main factor” in the scrapping of fees.

Australia is the example of a post-graduation income-contingent repayment system that is usually held up by supporters of fees in Germany, he says. But, according to Philippi, “there is already an instrument that we would say is even more [aligned with] justice – and that’s taxation”. Progressive income taxation means “those who are richer have to pay more”.

But Philippi also believes that the fees debate “will be revived in future. Because there’s still a lot of neoliberals and conservatives left who don’t want to pay for the social welfare state with taxation [and] who want a society in which…individuals pay for themselves.”

Germany’s federal government is currently a grand coalition, with the conservative Christian Democrats (CDU) and its Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union (CSU) reliant on support from the centre-Left Social Democrats (SPD). The education and research ministerial post is held by the CDU. The ministry’s impressive Berlin building, opened in 2014, is on the banks of the River Spree, in the government quarter, and Quennet-Thielen – whose state secretary post is comparable to that of a UK permanent secretary – enjoys an office with views across the river to the Reichstag building’s glass dome.

Quennet-Thielen says fees are “fully within the competence of…the Länder. Therefore there is no formal position of the federal government in that regard.”

She goes on to say: “With regards to what is going to happen in the future [on fees], I don’t dare to predict. We clearly see constantly increasing funding needs. Certainly all university presidents will tell you ‘we need more money’…We are absolutely used to that.

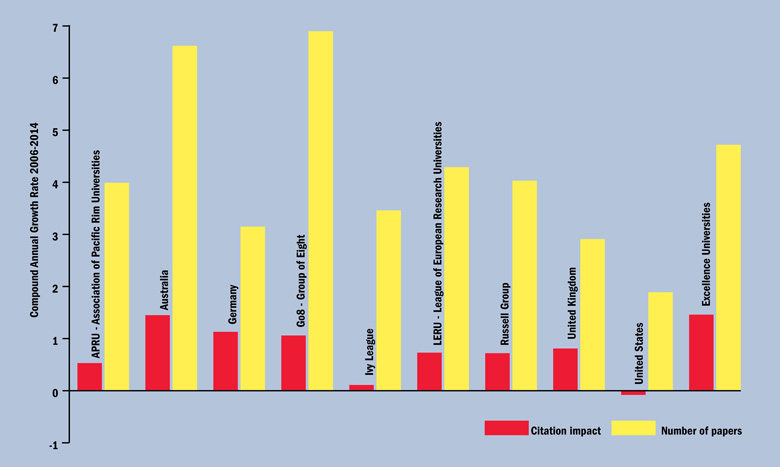

Publication quality and volume

Note: Compound annual growth rate is a business and investing specific measure of growth over a multi-year period.

Source: Scopus

“But I think you have to take into account how expenditure for higher education developed in this country, in [contrast] to other countries.

“In the past 10 years, the funding for higher education increased by one-third, at a time when in most other countries it decreased.” She notes that in England “the funding for universities from government was reduced, with the consequence that fees and tuition increased. The same happened in the US. Whereas here, both the federal government and the states responded to increasing needs – maybe against the background of realising how important higher education is for the individual on the one hand, but also for society and the economy at large.”

Federal and state funding for higher education was €18.4 billion in 2005, rising to €23.8 billion in 2011 and €26.7 billion in 2013.

“The Ministry of Education and Research was one of the very, very few [ministries] that had increases in its budget even during the financial crisis…There are a lot of countries and universities…that envy their German partners for the very stable source of funding that they have,” Quennet-Thielen says.

She stresses that federal and state governments have combined to support expansion. Under the so-called Higher Education Pacts I and II, the federal government provided the Länder with €8 billion to fund 425,000 extra university places between 2007 and the end of 2015 – although the rectors’ conference has said that student numbers were actually far higher than budgeted for. The federal government is also investing €200 million under the Quality Pact for Teaching in 2016, aimed at improving student-to-staff ratios and training for lecturers.

On the Excellence Initiative, Quennet-Thielen is explicit that “more differentiation within the university system with regard to research” is one of the aims “successfully” achieved. And while acknowledging that it is difficult to prove cause and effect, she adds that “if you look to the percentage of foreign students, professors…all these numbers went up”.

Olbertz is also an enthusiastic supporter of the initiative, saying it meant that German academia “learned to accept that you need vertical differentiation if you want to keep…the ability to be successful in international competition. There’s no other way.”

However, Kehm cautions that the Excellence Initiative “cannot solve all the problems of the system”, such as the high proportion of German academics on short-term contracts. And Ulrich Teichler, professor in the International Centre for Higher Education Research at the University of Kassel, says that the initiative’s significance has been “overblown”, calling it “peanuts” in financial terms. He suggests that German research performance improvements may have begun earlier, with increased publication in English and “smarter” publishing strategies.

Data from Elsevier’s Scopus database compiled for THE (see graphs) show that the 11 German universities selected for institutional funding in the second round of the initiative have performed strongly on citation impact since 2006 when judged against key international comparators – and against German universities in general. On the other hand, Excellence Universities still perform poorly compared with the UK’s Russell Group on their ratios of students to academic staff and international co-authorship, according to THE rankings data. And a 2015 analysis by Nature found that while German research performance has improved in the initiative’s wake, “some universities less favoured by the initiative have improved just as quickly as the elites when it comes to generating highly cited research”.

In January, the International Expert Commission on the Excellence Initiative, led by Dieter Imboden, emeritus professor of environmental physics at ETH Zurich, delivered its evaluation of the programme to the federal and state governments. The verdict was “very positive” (see 'In search of excellence: how the initiative operates' box, below), and the commission recommended that the project be continued with funding levels at least as high as they are now. The federal government and the Länder must agree on their response to the report this month. But whereas the states’ contributions are still to be discussed, the federal government has already announced it will press ahead.

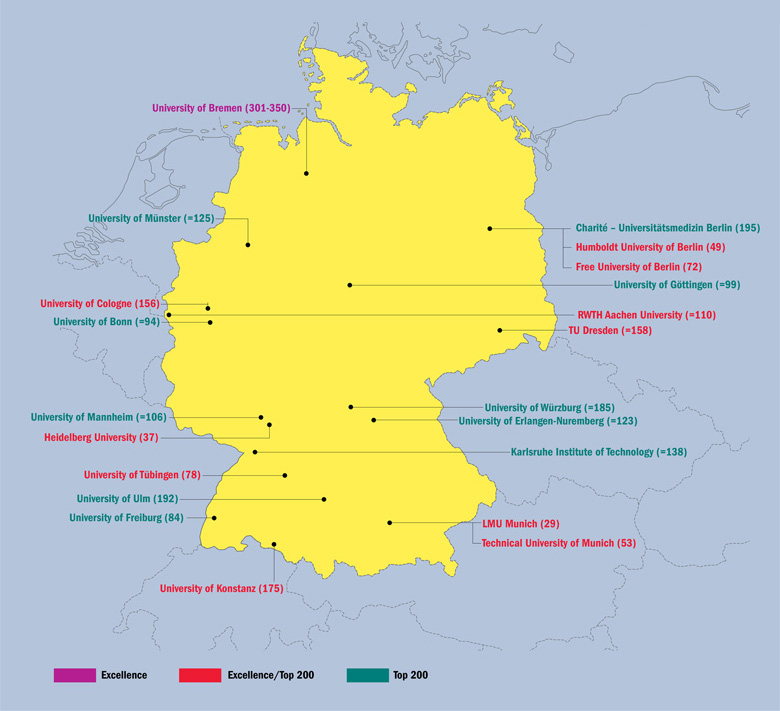

LMU Munich’s central buildings are on Ludwigstrasse, the grand avenue commenced in 1816 by order of King Ludwig I of Bavaria, next to a hefty 19th-century triumphal arch dedicated to the Bavarian army. The highest-ranked German institution in the THE World University Rankings 2015-16, at 29th, it has “benefited to a very large extent from the Excellence Initiative, in terms of additional funding, additional visibility and additional reputation”, according to its president, Bernd Huber.

“If you consider that in the first round they [federal and state governments] spent less than €2 billion, they really got a bang for their buck,” he adds, noting that the Excellence Initiative has “changed the perception of German universities all over the world”.

German universities in the excellence initiative and the THE World University Rankings 2015-16 top 200

Huber says that “research clusters” (see 'International colleagues are right to be ‘afraid’: Munich’s systems neurology cluster' box, below) that were developed under the initiative have allowed LMU to attract researchers from institutions including the University of California, Berkeley and University College London, and have delivered “a boost in terms of research output”.

As head of a prestigious, wealthy university in conservative, affluent Bavaria, you might expect Huber to be beating the drum for fees – but he is not (at least, not for THE’s ears). “It was such a political failure, this whole exercise…It’s very clear there is no political party, no politician, who is currently in favour of reintroducing tuition fees,” he says.

While additional income from tuition fees “might help us in terms of international competition”, Huber adds that “there are arguments in favour of not imposing tuition fees as a kind of competitive instrument”. For instance, the absence of fees helps to draw international students to Germany who might “stay here and increase the labour force”, he says.

Despite its lofty position in the World University Rankings, LMU, with its 50,000 students, continues to exemplify another two related features that further distinguish the German system from those of the US and UK: its much lower levels of admission selectivity and inter-institutional hierarchy.

According to Huber: “It’s not so important which university you have attended…You can say very roughly if you do an undergraduate degree you will get a very good education at every university in Germany.”

The FZS’ Philippi stresses the importance of this philosophy: “Students demand that every member of society has [the right] to get the best education possible. If we have elite universities where only a small part of society has the possibility to study, that would be socially selective,” he says. And his objection to the Excellence Initiative is that it is driven by “the political will to differentiate all the universities – to have some that are better than others, to create those differences which, in German history, were not there”.

And Kehm suggests that in the initiative’s wake, Excellence Universities are indeed “getting more selective”.

International interest is growing in a range of Germany’s alternative models, including its economy, which weathered the financial crisis better than most and to which education makes a key contribution.

Quennet-Thielen says Germany remains strong in “high-end industry production, more than other countries. We haven’t put so much emphasis on services only…And the past 10 years have shown this was not the worst strategy to take.”

She adds: “The innovative power of German industry certainly has to do with the long-standing tradition of cooperation [with] universities, including what we call universities of applied science, the Fachhochschulen.”

But Germans have options beyond universities, with the nation’s internationally respected vocational education system an alternative route into good jobs. Quennet-Thielen says that there is a debate on whether it would be “the right track for the country to have ever higher numbers of university students. Would the natural consequence be that you have fewer people in vocational training? And very clearly our vocational education and training…has proven to be also a pillar of our economic strength.”

This picks up on an important point. As Germany’s successful, publicly funded higher education model continues to grab international attention, it should be acknowledged that it is balanced by a strong vocational sector. It also relies on the tax take from a strong economy – and on a society willing to pay higher income taxes in general. Electorates in other nations have made different choices, some will argue.

There is the possibility that Germany’s own model may change, if pressure to reintroduce fees revives. However, the structure of German federal democracy – where consensus is key – remains a factor weighing against such controversial change.

But if the Excellence Initiative restores German universities to the international renown they once enjoyed, it could undermine the common global assumption that tuition fees are a precondition for international competitiveness.

That, of course, is predicated on Germany’s being able to accommodate any tensions between the initiative and its egalitarian higher education traditions. But if Humboldt is anything to go by, a happy compromise is not impossible. In the lobby, beneath the Marx quote whose GDR heritage once caused such controversy, is the HumboldtStore. Alongside the standard-issue university merchandise, small busts of Marx are on sale for €27.

In search of excellence: how the initiative operates

The first phase of the Excellence Initiative ran from 2006 to 2011, providing €1.9 billion of funding. The second phase started in 2012 and is scheduled to conclude in 2017, having allocated €2.7 billion.

The project, currently 75 per cent funded by the federal government, is run by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the German Council of Science and Humanities (Wissenschaftsrat). The aim, as defined by the DFG, is to “promote top-level research and to improve the quality of German universities and research institutions in general, thus making Germany a more attractive research location, making it more internationally competitive and focusing attention on the outstanding achievements of German universities and the German scientific community”.

The project is divided into three funding lines. One, for graduate schools, aims at promoting young researchers. Another is for Excellence Clusters: specific projects carried out in partnerships between institutions, including the non-university research sector. One of the aims of the initiative is to promote collaboration with institutions such as Max Planck Institutes, which, according to Cornelia Quennet-Thielen, state secretary for research and higher education in the German government, are “an important feature of our overall system of science and research, which sometimes is undervalued and under-represented – in [world university] rankings for example”.

In the second phase of the initiative, 44 institutions were awarded funding either for graduate schools or to participate in a cluster. But it is the 11 universities that gained “institutional strategy” funding – the initiative’s third funding line – that have received most attention, with some terming them the Excellence Universities.

The recent Imboden report on the success of the initiative recommends dropping the line of funding for graduate schools for the next phase. This would leave refined versions of the initiative’s other two lines of funding: one providing longer-term funding for seven to eight years for “high risk, high gain” research, and another funding “the 10 best universities” – to be determined by a research ranking – with about €15 million each over the same period. To allow for time to develop the successor programme, the scheduled end of the current second phase should be extended from 2017 to 2019, the report adds.

“While it is not possible to demonstrate an increased differentiation of the German university system as a whole as a consequence of the Excellence Initiative, bibliometric investigations show an impressive qualitative performance regarding publications stemming from Excellence Clusters,” the report says.

International colleagues are right to be ‘afraid’: Munich’s systems neurology cluster

The Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology (SyNergy), one of the 43 clusters currently funded by the Excellence Initiative, researches “how neurological diseases emerge from the interplay of degenerative, immune and vascular mechanisms”.

Led by LMU Munich in partnership with the Technical University of Munich, the project also includes participation from the German Centre for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), the Helmholtz Centre Munich (HZm) (German Research Centre for Environmental Health) and the Max Planck Institutes for Biochemistry, Neurobiology and Psychiatry.

Christian Haass, chair of metabolic chemistry at LMU, is joint coordinator of the cluster, housed in brand new buildings in a Munich suburb. He says that the competition for funding under the Excellence Initiative was “brutal”, meaning that “only the best of the best could survive”.

The cluster brings clinicians to work alongside basic scientists, giving the latter access to patients with Alzheimer’s disease, for example. Imaging technology used by the clinicians – what Haass calls an “outrageously expensive” synchrotron – can now be employed by the scientists.

This means that the scientists do not have to conduct analyses that kill laboratory mice and can thus study the development of the Alzheimer’s pathology over longer periods of time.

“Without having clinicians in the same building, [such research] would never work,” Haass says. US and UK colleagues are “all aware of what’s happening” in Germany under the Excellence Initiative, he adds. “They are afraid. They should be. Things have changed.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: An alternative route

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?