Many academics put special emphasis on notions such as subversion and transgression. But have we subjected them to enough critical scrutiny?

I started thinking about this recently while listening to a radio show. The theme of this year’s gala at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art was “camp”, so the host was talking to two experts about what it meant. Asked for a definition of the style, both readily responded by using the word “subversive”. When the host pointed out that many of the people wearing such styles were very much part of the Establishment and had made a lot of money from their fashion, one guest seemed a bit surprised, saying she’d never thought about that, but then doubled down by insisting that it was still subversive.

For those on the academic left, shaking things up, queering them, deconstructing binaries have all seemed worthy ways of undermining power and injustice. So transgression, subversion, flamboyance, jubilance, disruption have all been key watchwords. Book titles featuring such words abound. In one, Magdalena Cieslak and Agnieszka Rasmus’ Against and Beyond: Subversion and Transgression in Mass Media, Popular Culture and Performance (2012), punk and goth cultures are seen as the “releasing of revolutionary desire by transgressing the limits of capitalism…subverting the norm by cultivating new, often deviant eroticisms”. A 2015 article in the Journal of Business Research even argues that heavy drinking in the UK is actually a form of transgression and so resistance, since “under neo-liberal alcohol policy, government campaigns ostensibly seek to control un-sanctioned, carnivalesque drinking practices that potentially subvert official rules and controls”.

For me, an emblematic low point in this style of subversive politics came at a conference when an anti-neoliberal colleague approvingly presented a film by some white Californian art students. In it, one of them dressed as Ronald McDonald and confronted various hapless store managers of the franchise as they travelled from Los Angeles to Mexico City, claiming that their bogus Ronald had a right to eat free hamburgers. As the embarrassed working-class, mostly Latinx servers tried to explain to the camera pointed in their faces how they couldn’t comply, the jubilant and flamboyant art students went into the bathroom and exuberantly unfurled rolls of toilet paper into the air. Clearly, neoliberalism was done for.

Yet in an age in which bad leaders exemplify disruption, transgression, subversion and flamboyance, how can such behaviours lead us to greater social justice? You can’t get more flamboyant than quasi-despots such as Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Rodrigo Duterte, Boris Johnson and Matteo Salvini. In fact, their appeal is based on their larger-than-life personality performances with outrageous hair and bare chests. Likewise, they subvert norms and revel in transgressing laws and ethics. Why did we think that these strategies were inherently progressive and liberatory?

So where did this all start? There was a time when political action involved changing laws, voting enemies out of power and electing people who might institutionalise progressive change. The civil rights movement and ban-the-bomb demonstrations tended to be sombre affairs in which non-violent resistance was the rule and changing unjust laws the goal. And they certainly achieved some important successes: massive civil rights legislation improved the legal and daily reality of many oppressed people.

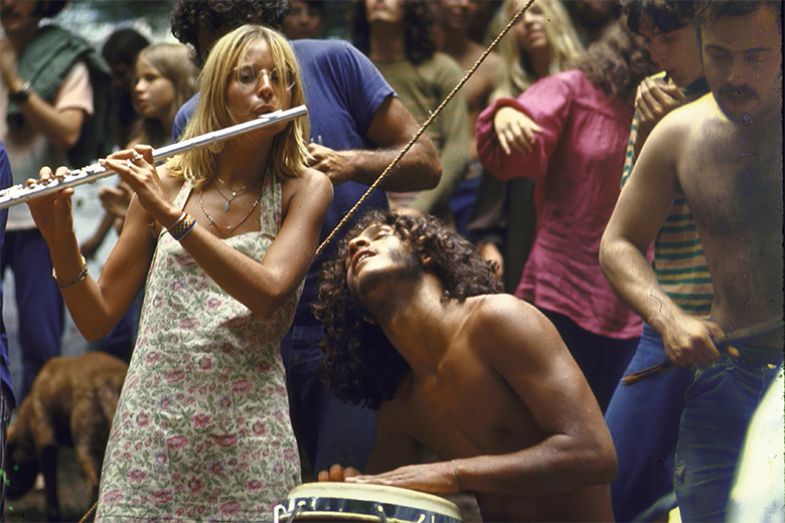

Then, somewhere along the line, those attempts to bring about concrete change gave way to what you might call cultural sabotage. If I look to my own life, this shift began in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when revolution seemed a few demonstrations and acid trips away from coming about. The counter-culture – sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll – offered rowdy insult to the face of staid but dangerous mainstream government, including its evil axis of power, the FBI, CIA, police and armed forces.

With street protests, be-ins and sit-ins, raucous reactions to injustice held out a hope that the “Establishment” would capitulate in the face of a massive cultural upheaval. The times were changing and the old order was rapidly fading, as Dylan told us.

When LGBTQ people formed the ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) group in 1987, transgression, subversion, camp and flamboyance furthered the idea that behaving badly could change the world. And it did to some cultural and social extent. But elites were able to adapt and remain comfortably in power.

Academic discourses of the time easily slipped into this mindset. Marxist criticism, especially that of Antonio Gramsci, Louis Althusser and the Frankfurt School, while advocating socialism and revolution, focused on concepts such as hegemony and state intellectual apparatuses whose role in shaping consciousness needed to be critiqued and challenged. However, when it came to change, now that Stalinism had destroyed the idealistic side of communism, the hope was for some kind of vague, unspecified transformation of the social, political and cultural surround.

Foucault’s popularity was both a driver and a result of these tendencies. Always against power in principle, he had great difficulty coming up with what to do about power in reality. His academic works detailed how power operates within bodies of knowledge – medicine, psychiatry, penal systems – but had trouble locating the weak points within discourses that could break down the power structures. Academics influenced by him could do little but detail instances of power and then improvise when it came to dismantling those forces.

While I have been talking about my own generation, many of whom remain progressive, we were also the teachers of a younger generation of scholars who now are in their thirties and forties. Many of them have been strong critics of neoliberalism, well able to list an array of malpractices that were hallmarks of a new phase in capitalism, but have again provided little in the way of policies for halting those practices. Bringing down neoliberalism seems as difficult as doing without the fruits of its abusive behaviour such as iPhones and computers.

It would be remiss to omit the accomplishments of the #MeToo, Black Lives Matter and Occupy movements, to name a few, that have relied to some degree on subverting and transgressing. And of course in tyrannical, racist and patriarchal societies where ordinary protest and legislative processes are blocked, disruptive behaviour has a role to play. But neoliberal capitalism has often been able to absorb – and even profit from – subversion and transgression.

While both these generations have gone in for a rigorous critique of everything, we seem to have failed to put under the microscope in any meaningful way the concepts of “transgression” and “subversion” themselves. We’ve just taken these for an unmitigated good. But might it be that our good has become a bad, and that being subversive or transgressive is a tactic that anyone can use regardless of political affiliation? Isn’t someone like Donald Trump simply a good student of the lessons of his generation? His mistrust of news media is a direct correlate to our suspicion of the mainstream press. Many of us preferred subversive outlets such as The Nation, In These Times, Mother Jones and Rolling Stone. His preference is for news sources that point to the deep state that Steve Bannon sees as the equivalent of “the Establishment” those on the left have questioned and seen the need to subvert.

Of course, not all academics favour the ideology of subversion and transgression. In scientific and technological subjects such as biochemistry or engineering, relying on the past while carefully innovating in the present is more the norm. If an engineer is subversive, a plane goes down or a bridge collapses. The risks might seem lower for those in the humanities. But are they? Raising a generation or two of scholars bent on subverting, transgressing and being flamboyant has perhaps left a gap in the possibilities for specific social change and the remediation of injustice.

So what would it mean for academics to move away from a politics of subversion to one of construction? Let’s face it, subversion is easy. It’s much easier to write a snarky book review than a positive one. But passing legislation that redistributes wealth is more effective in combating income inequality than dancing rudely, naked and tattooed, in front of capitalists. Marx once advocated “a ruthless criticism of all that exists”. In adopting this position, many academics forget to praise what works. We teach our students to critique, but we don’t emphasise the importance of constructing viable alternatives. If the humanities could be seen as the place where one goes to find specific ways of building up rather than tearing down, we might be doing a better job of education. How many of us teach our students to create concepts rather than deconstruct them?

Many leftist academics have a special spot in their hearts for activists without actually specifying what active act they are blanketly praising. For many, rowdy acting out constitutes activism. But effective activism may involve the many tedious actions involved in getting a law written and passed. Could the academic left be subverting itself by placing more emphasis on subversive activity than on specific steps towards concrete change?

In a sense, these politics of transgression and flamboyance came about as part of the baby-boomer generation’s fight against the Second World War and Cold War generation. As a member of that generation, I think we saw ourselves as the idealistic youth fighting an “old order” that was both antiquated and aged. Exuberance, defiance and a somewhat self-satisfied but unambiguous critique defined us as the teens fighting the parents. Could it be that we, now greyer but not necessarily wiser, still see ourselves as the kids? If so, does Trump’s childishly petulant behaviour require that we behave like the adults in the room and adopt the appropriate countermeasures? A new generation of academics might be able to take on the role of being for social justice and economic equality by doing the things that grown-ups do to make sure that the refrigerator is stocked and the kids are safely in bed. It might mean turning down the noise and rolling up the sleeves to make the efforts required for true change. Last on the to-do list would be expressions of flamboyance, transgression and subversion.

Lennard Davis is distinguished professor of English at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

后记

Print headline: Turn down the noise, roll up the sleeves

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?