Fifteen years ago, Jim O’Neill, then chief economist at Goldman Sachs, coined the term “BRIC” to designate a group of four large, rapidly developing countries – Brazil, Russia, India and China – whose growth he expected to drive the global economy over the coming decades.

In 2011, he noted that all four had exceeded his expectations: their aggregate gross domestic product almost quadrupled during those 10 years, from about $3 trillion (£2.45 trillion) to between $11 trillion and $12 trillion.

This combined GDP increase was more than twice that of the US.

By 2009, the group had become an official entity, and the following year, it admitted South Africa and changed its name to the “BRICS”. Then, in 2013, O’Neill began talking up the “MINT” countries – Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey – as the next emerging economic giants.

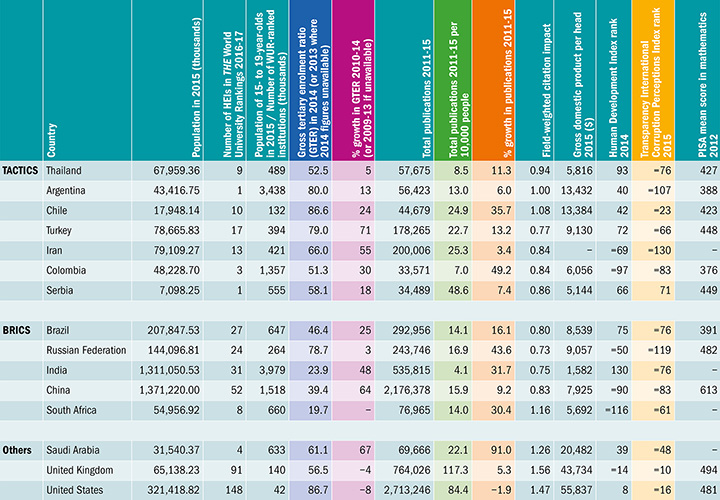

However, while the nations in both these groups are experiencing rapid economic development, their higher education progress is more mixed. Less than a fifth of university-aged people in South Africa and less than a quarter of those in India are enrolled in higher education, for example (see table, below).

Research by Times Higher Education, in partnership with University College London’s Centre for Global Higher Education (CGHE), suggests that when analysis is confined to elements relating to higher education, a somewhat different set of developing nations can be identified as potential future stars. These are Thailand, Argentina, Chile, Turkey, Iran, Colombia and Serbia – which, in the spirit of O’Neill, we are calling the TACTICS.

In all these countries, GDP is below $15,000 per head, at least half the youth population is enrolled in higher education and participation grew by at least 5 per cent between 2010 and 2014. In addition, the TACTICS are increasing their research publication output, already publish at least 30,000 papers a year, have at least one university in the THE World University Rankings 2016-2017 and have a field‑weighted citation impact of at least 0.75 (compared with a world average of 1.0).

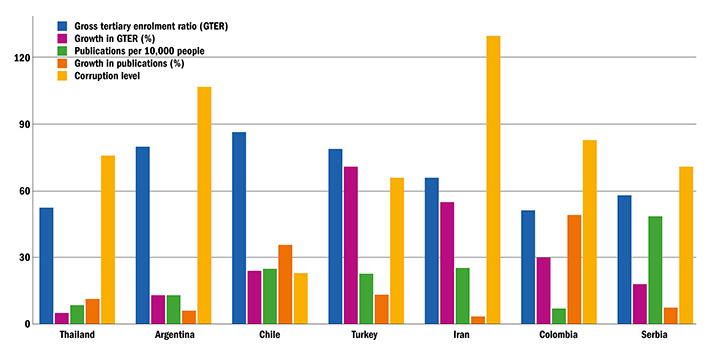

Nicki Horseman, lead higher education data analyst at THE, says that as a group, the TACTICS have a higher average gross tertiary enrolment ratio (GTER) – the proportion of university-aged students enrolled in higher education – than the BRICS. The TACTICS also have a higher average field-weighted citation impact, which compares citation counts to the global average in the relevant fields and is considered to be a measure of publication quality.

“The BRICS are definitely showing growth in GTER and publications, but the TACTICS are a stratum above,” she says. “That’s the thing that really stood out for me: that these countries that we haven’t really discussed before are, on average, better than the BRICS in terms of higher education.”

Group strengths and weaknesses

Note: See table below for full definitions and exact figures

TACTICS and BRICS compared

Sources: Elsevier, World Bank, United Nations, Unesco, Transparency International, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

Chile, Argentina and Colombia

Of the individual TACTICS countries, Chile has the highest GTER, at 86.6 per cent, while participation is growing fastest in Turkey, where it rose by 71 per cent between 2010 and 2014. Chile ranks better than even the UK when it comes to the number of 15- to 19-year-olds in the country per university in the World University Rankings – although, of course, UK universities tend to rank much higher than Chilean ones.

J. Salvador Peralta, associate professor of political science at the University of West Georgia, says that the large and growing populations of 15- to 24-year-olds in Chile, Argentina and Colombia could be a “source of strength” for those countries’ higher education systems, and all three have been “striving very hard to develop a quality assurance system”.

But he says that none of the nations has found a “really effective way of capitalising on that demographic growth”. Colombia, for example, spends only 1 per cent of its GDP on higher education and has not invested enough in loans, grants or other forms of financial aid that could subsidise tuition costs, he says.

In terms of publications, Colombia has the lowest output of the TACTICS, both at an absolute level and per head of population, but it has seen the fastest growth: 49 per cent since 2011. Chile recorded the second-highest growth, 36 per cent.

Simon Marginson, director of University College London’s Centre for Global Higher Education and professor of international higher education at the UCL Institute of Education, adds that Chile spends more on research and development relative to its size than any other Latin American country except Brazil. Argentina, meanwhile, has a “very strong scholarly culture in a lot of disciplines”.

However, Marginson observes that although Argentina has been a “fairly wealthy South American country since the turn of the 19th century and at one stage was one of the richest countries in the world in terms of its GDP per head”, it “slid into economic and political weakness” after the First World War and has “never really recovered from that downward slide”.

Peralta adds that while Argentina has committed to spending at least 6 per cent of its GDP on education, which would put it among the highest spenders in the world, its government recently decided to cease funding the Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation, which supported research and development. And, in May, public university teachers in the country went on a six-day strike to demand greater investment in higher education, improvements in infrastructure and wage increases amid a rapidly rising cost of living.

Indeed, all Latin American countries are likely to find many rocks along the path to higher education excellence. In general, Marginson says, its nations have a “stronger” academic culture in social sciences and the humanities but a “weaker science performance”. He attributes this to a lack of equipment and the absence of large research groups – although he suggests that this might improve as Latin America’s economies develop further.

On that point, Peralta laments the continent’s high susceptibility to “booms and busts”, which affects university funding and makes international recruitment harder. That said, he notes that the University of Chile and the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile have been successful at attracting international academics, which has helped them to improve the quality of their teaching, to build PhD programmes and to boost research productivity. But, in general, neither Latin American governments nor individual universities are looking to succeed in “world terms”, according to Marginson, who says this explains why Argentina and Colombia have just four representatives among the 980 universities in THE’s rankings – three of which are Colombian.

“Rankings have been a big driver of improvement, especially in research, and Latin America tends to be self-referential and rather suspicious and distrustful of the world standard notion,” he says. “[It doesn’t] reward people strongly for success in world terms. [It doesn’t] have publication incentives to the same extent as universities in other non-English language environments.”

Improving Latin America’s relatively low publication output, Peralta says, is also likely to be hampered by poor English-language proficiency and a lack of research training. The “vast majority” of scholars outside the continent’s top universities, he notes, do not hold a PhD, and many have only a bachelor’s degree; a mere 4,000 of the nearly 50 million people in Colombia have a doctoral degree. This means that most scholars lack the credentials to be competitive at submitting papers to peer-reviewed journals and they focus instead on teaching.

One worry for Chile is that, historically, the cost of its higher education has been among the highest in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, with upwards of 80 per cent of it borne by students themselves, according to Peralta. Last year, however, after huge and prolonged demonstrations by students, the government announced that it would scrap tuition fees for students from the poorest 50 per cent of Chilean families. Andrés Bernasconi, director of the Center for Studies in Education Policy and Practice at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, says that the aim of the reform is to increase the number of poorer students attending university, but the decisions over which institutions and which students will be eligible for the new scheme are still being thrashed out in the country’s parliament. And he contends that Chile does not have the money to pay for the universal free university education that the student protesters were demanding.

Even if the country had the resources to fund it, free higher education for all does not necessarily create an equitable system, says international higher education consultant Liz Reisberg, noting that in Argentina, where universities are free and open to all, students from poor backgrounds are very unlikely to finish their degrees.

“Most people in Argentina think open enrolment is the way to make [the system] more equitable because everyone can get to the starting line. But to me, it’s much more complicated than that,” she says. “Equitable means doing something in the earlier grades [at school] to make sure people are starting with equal opportunities and equal potential to be successful.”

She adds that each of the three Latin American countries in the TACTICS group has experienced rapid growth in university enrolment because it is viewed as a “mechanism for socio-economic mobility”, but she warns that the higher education sector will “have to come to terms with lower-quality institutions”.

Peralta also questions whether Argentina’s “noble” free university model is sustainable in light of the country’s recent economic downturn, while Marginson says that there remains “a significant group of relatively poor families” in Latin America that do not participate in higher education to the same extent as equivalent families in East Asia, where higher education systems have improved immeasurably in recent decades.

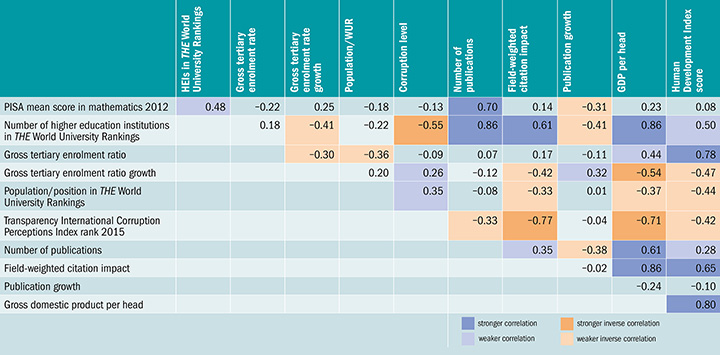

Correlations between selected factors

Notes: A correlation of 1.0 is a perfect correlation; a correlation of -1.0 is a perfect inverse correlation. A correlation of 0 indicates no correlation. A high HDI score indicates a high level of human development. A high Transparency Index score indicates a high level of corruption. The correlation is generated by examining all the countries listed in the ‘Markers of progress: TACTICS and BRICS compared’ table, above

Serbia

Serbia is fairly unusual among European nations in having a GDP per capita that is below the world average. In addition, its gross tertiary enrolment ratio is much lower than that of Argentina and Chile, but it has grown by 18 per cent between 2010 and 2014 and, at 58 per cent, outstrips that of all the BRICS except for the Russian Federation.

Among the TACTICS, Serbia also has the highest mean maths score in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which measures attainment at the age of 15. This suggests that its students may be better prepared by the school system than those in most other TACTICS nations.

However, Martina Vukasovic, a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Higher Education Governance at Belgium’s Ghent University, says that the biggest growth in enrolment in Serbia took place during the 1990s. More recent growth is largely illusory, primarily a result of 2005 legislation that incorporated many institutions previously designated “post-secondary institutions” into the higher education system. But private universities have also been on the rise and now cater for about 10 per cent of the overall student population, she adds.

Other problems Serbia faces include a low number of doctoral and postdoctoral positions and excessive tribalism among university departments, which hampers opportunities for cross-disciplinary research and teaching, Vukasovic says. But the country has implemented several higher education reforms since the end of Slobodan Milošević’s autocratic rule in 2000. According to Vukasovic, these include the introduction of a bachelor’s, master’s and PhD degree structure and the establishment of a quality assurance system. Meanwhile, degree completion rates have risen even as enrolment rates have increased. And there is clear scope for the volume and quality of Serbia’s research output to increase, given that it is still recovering from the international isolation into which, according to Vukasovic, Serbian universities were plunged in the 1990s, amid the outcry over the country’s role in the wars in the former Yugoslavia.

Thailand

Thailand has seen the lowest growth in participation rate among the TACTICS, but Simon Marginson, director of University College London’s Centre for Global Higher Education, says that its overall level of 52.5 per cent is still relatively high given the country’s GDP. He adds that it is likely that participation will continue to increase because the country is now “rich enough” for the modernisation processes of wage-based labour, city living and greater focus on education to move forward.

When it comes to research productivity, Thailand has the third highest output of the TACTICS countries, representing a growth of 11 per cent between 2011 and 2015 – although in terms of output per head of population, only Colombia and India record lower rates than Thailand among the TACTICS and BRICS.

Marginson notes that Thailand’s research output has increased even though its government has not made a concerted effort to internationalise campuses, improve university performance or develop world-ranked institutions. “The politics is very contested and unstable in the past decade, and the Ministry of Education has not been particularly well focused on higher education,” he says. “But there’s a lot of private and public institutions: both sectors are quite strong, and it’s normal in Thailand for middle-class families to go to university.”

An analysis earlier this year by the higher education consultant William Lawton found that, despite the governmental inattention, links between Thailand and overseas universities have grown in recent years. Christopher Hill, associate professor in the Faculty of Education at the British University in Dubai, who worked on the study, says that Thai universities are looking to increase international collaboration as a vehicle to boost their research productivity – a push that is helped by the fact that many academics in the country were educated at universities in the UK and the US.

It is also notable that, among the TACTICS, Thailand has the third highest field-weighted citation impact. Its average of 0.94, just below the global average, puts it above all the BRICS except South Africa.

However, Hill says, producing high-quality research is something that South Asia in general struggles with, and many universities in the region aim to compete in international rankings “without necessarily having the internal capacity to do so”.

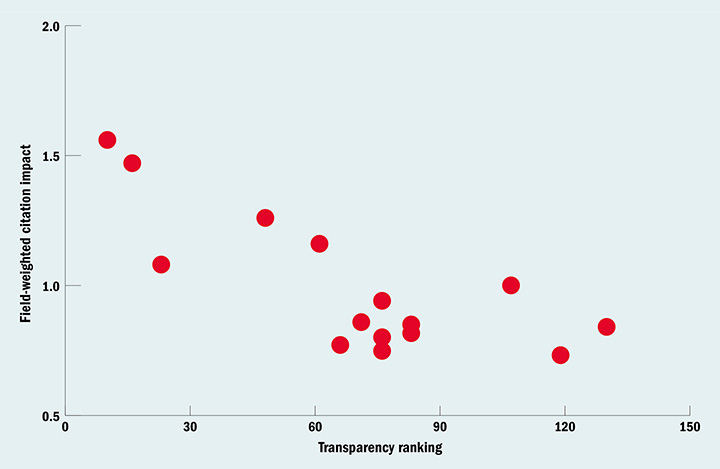

How research quality correlates with corruption levels

Note: Each dot corresponds to one of the countries in the ‘Markers of progress: TACTICS and BRICS compared’ table, above

Iran

Iran’s universities have had “immense success” in research in the hard sciences, and there are few global equals of its “rich intellectual tradition”, according to Arshin Adib-Moghaddam, professor in global thought and comparative philosophies and chair of the Centre for Iranian Studies at Soas, University of London.

“In terms of philosophy, art and poetry, the country is unique, no doubt. The combination of this blessing of history and the human resources [that Iran] boasts today offer an array of untapped opportunities for global culture,” he says.

Iranian universities need to build international collaboration to “progress even further”, he says, adding that prospects in this area have improved significantly since the lifting of sanctions in January, in the wake of the international agreement on curtailing Iran’s ability to develop nuclear weapons – although US president-elect Donald Trump’s antipathy to the deal could call that into question.

Simon Marginson, director of University College London’s Centre for Global Higher Education, adds that education and research have been “fully embraced” in Iran as part of the country’s modernisation process since the 1970s, in a way that is not seen in other emerging economies. As a journal editor, he receives an “enormous number” of article submissions from researchers in both Iran and Turkey, which suggests that there is “pressure” on academics in those countries to publish internationally.

“The sort of science you see in East Asia [and] drives towards international publications in the social sciences [are] happening in Iran as well,” he says.

But Iran could yet be held back by a lack of meritocracy. Its public sector is the most corrupt among the TACTICS, according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, which ranks countries according to their perceived levels of public sector corruption. Adib-Moghaddam notes that Iranian academic appointments are made “in accordance with ideological convictions rather than merit, especially in the humanities and in the social sciences” – although he does not see corruption as a “major issue” in Iran, in comparison to other countries.

Marginson regards Iran’s lack of academic freedom and “victimisation of scholars” as a “worry”. He still has his doubts about “how mobile and open the passage of people and ideas is between Iran and the rest of the world”. And although “you can breed physical scientists reasonably rapidly…without working through all the questions around academic freedom in the humanities that Iran clearly has problems with”, Iran’s ongoing “contested” international standing and the fact that it is being “drawn into Middle East politics with both [the wars in] Syria and Yemen” will hold it back, he predicts.

Turkey

Turkey has an enrolment rate of 79 per cent: the third highest of the TACTICS and higher than any of the BRICS. That represents a massive 71 per cent growth in the past four years. But the country has the lowest citation impact of any BRICS or TACTICS nation except for the Russian Federation. Its higher education system is also a potential victim of political circumstances, as institutions are purged of supposed supporters of Fethullah Gülen, the cleric alleged to have masterminded July’s failed coup attempt against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

More than 1,200 academics have been sacked and all 1,577 university faculty deans have been required to resign, while their political credentials are examined. The government also decreed last month that, in future, all rectors will be appointed by the president: previously they were elected by university staff. Fears have been voiced that leading scholars could desert the country. In September, the Scholar Rescue Fund and the Council for At-Risk Academics said that Turkey is now the number one country for applications from under-threat scholars seeking safety in Western universities.

Despite Turkey’s relatively healthy ranking for corruption, Mehmet Ugur, professor of economics at the University of Greenwich, adds that a system of “perverse incentives, fear and frequent state interventions” has been the “hallmark of Turkish higher education” for many years.

Indeed, he sees the links between universities and the Turkish state as one of the key reasons – alongside their role in training the workforce for the country’s growing economy – for the recent expansion of higher education. The government, he claims, sees universities as tools for “indoctrinating the graduates and the population in general” to ensure that “Turkishness is embraced” and to guarantee obedience to authority.

“Given these motives and the speed with which the system has expanded, I think Turkey has a very inefficient system that I find very difficult to call higher education,” he says.

For instance, a “well-intentioned” government initiative to provide incentives for academics to publish research and gain citations has “degenerated into a scheme whereby people establish citation networks – ‘you cite me, I will cite you’ – to get the points necessary to have an increment in salary”, Ugur says.

“When the norms and values of higher education have been dented by state intervention”, reaction to incentives at the “micro level” also “becomes distorted”, he says.

后记

Print headline: The new breed on the charge