The Swiss National Museum in Zurich gets straight to the point in its section on the history of Switzerland. William Tell’s 14th-century rebellion against Habsburg tyranny and the 18th-century rise of banking can wait. Migration is first up.

The first display celebrates notable residents who were either not born in Switzerland or had at least one non-Swiss parent. The list includes Erasmus, Voltaire, Roger Federer and Albert Einstein (the last a graduate of, and professor at, both ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, and the University of Zurich).

The display goes on to explain that Switzerland was a poor nation of emigration until its industry and manufacturing flourished in the early 20th century, reversing the flow of people. Post-1945 waves of immigration into Switzerland included Italians, Portuguese, Turks and, most recently, people from the former Yugoslavia.

In 2014, foreign nationals made up 24.3 per cent of the nation’s total population, according to Swiss government figures. But not everyone buys into the museum’s liberal message on immigration. Long-standing tensions around the issue in some quarters of Swiss society recently produced an event with seismic consequences: the immigration referendum of February 2014, in which 50.3 per cent of voters backed limits on immigration from the European Union.

Although Switzerland is not a member of the EU or the European Economic Area, it subscribes to free movement of people as part of a series of bilateral deals with the EU. However, the right-wing Swiss People’s Party (SVP) opposes free movement and was responsible for bringing about the immigration referendum.

Immediately after the vote, the Swiss government decided that the result meant that it could not sign a deal on free movement with new EU member Croatia. This threw into jeopardy Switzerland’s entire relationship with the EU, which holds the free movement of people as an essential principle. In response, the bloc reached for the weapon closest to hand: the deal then under negotiation for Switzerland to participate in its latest research programme, Horizon 2020, as an “associated country”, which would have given it similar participation rights as EU member states.

Switzerland found itself outside Horizon 2020 and the Erasmus+ student mobility programme, being granted only a temporary reprieve by the EU with a “partial association” to the former scheme in December 2014. And the bloc insists that if the Swiss government has not formally ratified the Croatia protocol by 9 February 2017, Switzerland will be kicked out of Horizon 2020.

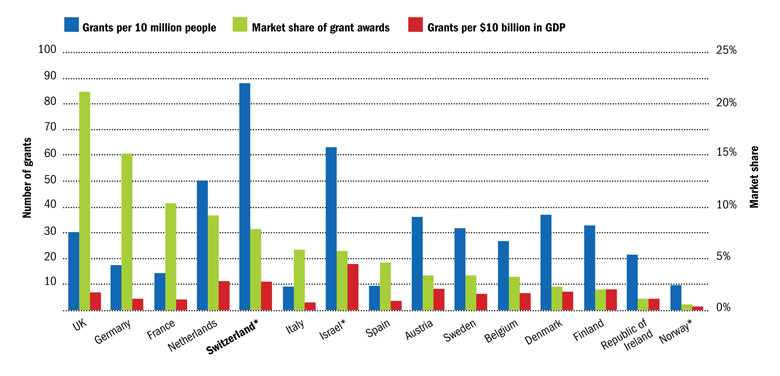

If that happens, Swiss-based researchers will no longer be able to compete for grants from the elite European Research Council, sometimes described as the Champions League of research. Swiss universities are conspicuous overachievers in capturing ERC funding given the nation’s population of just 8 million (see ‘Swiss overperformance in recent European Research Council grant rounds’ and ‘Funding success in all European Union competitive programmes, 2006-15’ graphs, below).

Swiss overperformance in recent European Research Council grant rounds

Notes: Countries are listed in order of market share of grants. Figures relate to the 2015 funding rounds of starting, consolidator and advanced grants. *Indicates associated country

Sources: European Research Council, World Bank

Among universities (as distinct from research institutes) whose researchers made more than 50 applications for ERC grants during the EU’s Seventh Framework Programme, which ran between 2007 and 2013, only three returned success rates of above 30 per cent. These were all Swiss: ETH Zurich (31.3 per cent), the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (30.3 per cent) and the University of Basel (31.3 per cent). As a comparison, the universities of Cambridge and Oxford had success rates of 25 per cent and 21 per cent, respectively.

But Swiss universities fear that exit from Horizon 2020 will inflict severe damage on their ability to attract leading researchers and, thus, weaken a nation that relies on innovation to maintain standards of living. Lino Guzzella is president of ETH Zurich, which, at ninth, is continental Europe’s highest-ranked institution in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2015-2016. “The problem is that innovation, research, education…has been taken hostage by politics – on both sides,” he says. “You tear down something that is useful for everybody: science, education…What more useful human activities are there than these two? And now exactly these two are penalised most; the first victims of these political disputes. It is totally unacceptable.”

Switzerland is among the models that the UK will examine as it tries to form a new relationship with the EU in the wake of its vote to leave the union. One option for UK universities is to lobby the government to press for associated country status, and Switzerland’s experience shows British higher education and policymakers the value of that status, which the Alpine nation first acquired in 2004. But it also demonstrates that negotiations over such status can be deployed by the EU as a weapon within larger political machinations.

Universities in the UK and across Europe reap the benefits of free movement for students and researchers – and thus for ideas. But Switzerland provides an example of how free movement and the climate of openness prized by universities can come under threat as voters’ anxieties about the downsides of immigration and globalisation are fanned by nationalist parties that may not see universities and research as priorities.

ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich are neighbours, close to the city centre but sitting on a hill above it, and the latter’s tower and the former’s dome compete to dominate the skyline. A funicular railway called the “Polybahn” clanks up from the city centre to ETH (“polytechnic” was part of the institution’s title when it was founded in 1855). From the broad terrace in front of ETH’s neoclassical main building, you can look down on the rooftops of the old town, against a backdrop of Lake Zurich and the distant Alps, which remain snow-capped throughout the summer.

What are the prospects for Switzerland remaining in Horizon 2020? And what might the consequences be if it is expelled?

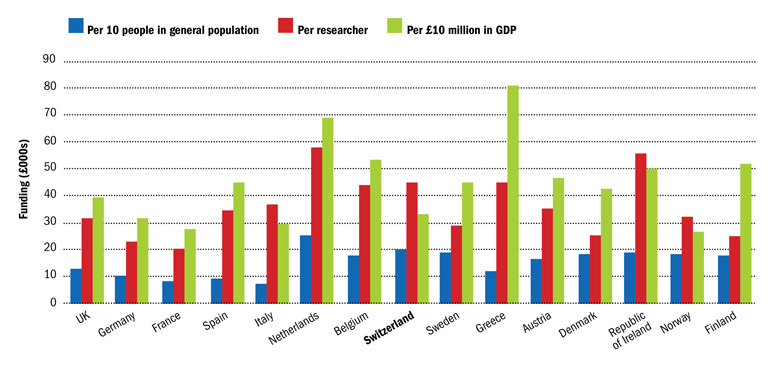

Funding success in all European Union competitive programmes, 2006-15

Note: Countries are ordered by the number of projects they participated in

Source: Digital Science

Michael Hengartner, president of the University of Zurich, also heads the Rectors’ Conference of Swiss Universities, known as swissuniversities. “The current positions of the two parties [the EU and the Swiss government] are such that if nothing changes in the position of one party or the other, the chances of us staying in are close to nil,” he says.

But a Swiss government research and education spokeswoman said that “finalisation” of ratification of the Croatia deal on immigration is “under way”. “The stated aim remains…full association to Horizon 2020 as of 2017.”

The Swiss government wants to maintain access to the single market but has proposed limitations on free movement, including a preference in hiring for Swiss and EU citizens already in the nation. But the EU is so far refusing to allow limits on movement – particularly now that any concession might encourage the UK to seek similar terms in its Brexit negotiations.

Failure to find a compromise on free movement could mean an end to Switzerland’s bilateral deals with the EU and, potentially, an end to free movement with the union’s member states, including key neighbours such as Germany. Given the gravity of the situation, Hengartner says that it is likely that “at some point in the not too far future” Switzerland will hold a second referendum on immigration. Hence, the Swiss government’s case to the EU might be “let us be temporarily associated” to Horizon 2020 until the outcome is known, Hengartner says.

The Swiss government’s proposed preference for domestic hiring is unlikely to find favour with the country’s universities. Guzzella says that at ETH, “close to 70 per cent of our faculty are not Swiss-born. If I cannot keep this mechanism that allows us to attract the brightest and most creative minds from all over the world, it will be more challenging for ETH to keep its position among the 10 best universities worldwide…I will do whatever I can to make sure that at least on the faculty level, but also on the senior scientist, postdoc and even PhD student level, we will still have the free movement of people.”

Under the “partial association” agreement, the European Commission granted Switzerland access to the first of Horizon 2020’s three pillars, known as “excellent science”. This means that Swiss researchers are eligible for key funding strands, including ERC and Marie Skłodowska-Curie grants. But, barring a few specific other elements, Switzerland was relegated to non-associated “third country” status in relation to the rest of Horizon 2020 (relating to “industrial leadership” and “societal challenges”).

Swiss universities are desperate to retain access to ERC funding beyond February 2017. Guzzella says that the money that comes with the awards is important, but he sets above that the reputational reward that successful researchers gain, in terms of enhanced esteem among their peers. “I sometimes call them micro-Nobel prizes,” he adds of ERC grants.

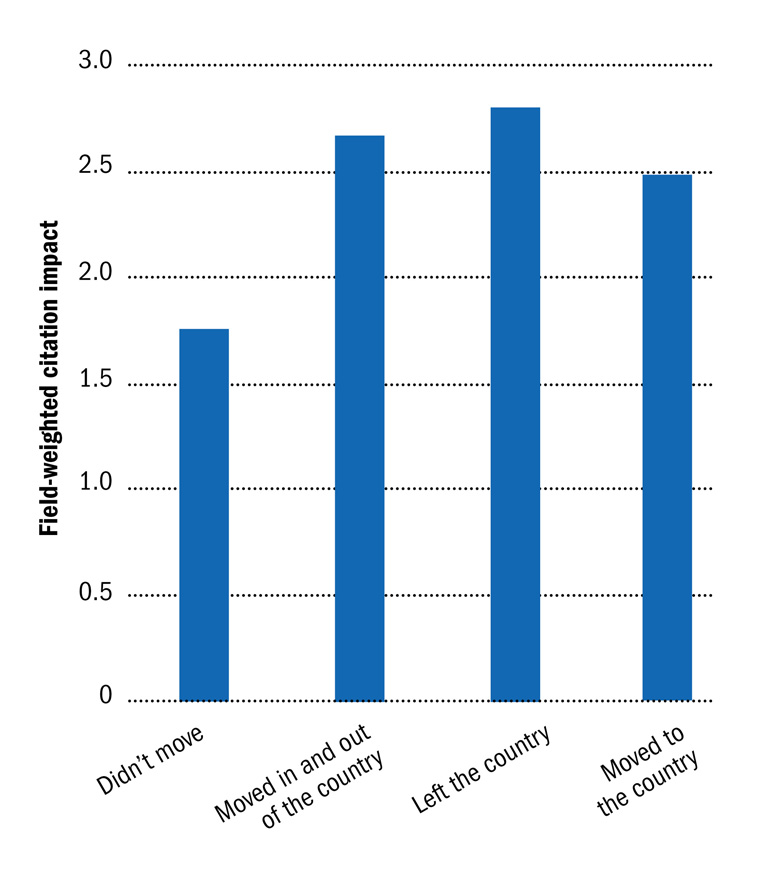

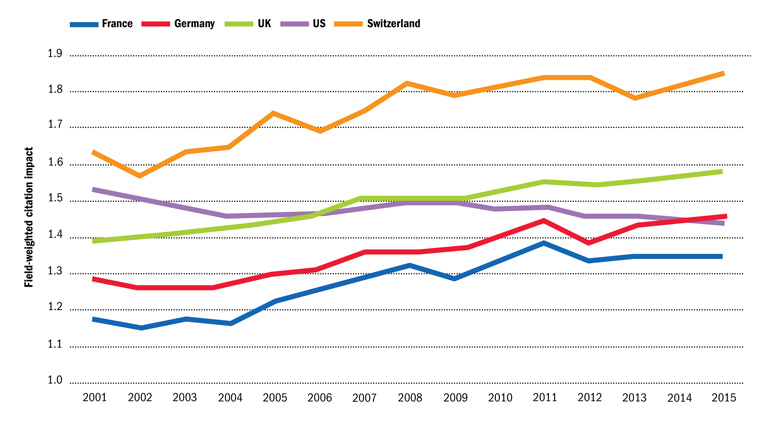

Citation impact of Switzerland’s researchers since 1996

Note: the global average is 1.0

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal

At ETH, ERC funding for individual researchers includes support for work on personalised medicine and genetic targeting. EU funding also underpins international collaborations such as the Climate-KIC (Knowledge and Innovation Community), which supports at ETH a leading centre in climate modelling and climate prediction, and OPERAM, a University of Bern-led project to use software to improve drug therapies for elderly patients with multiple chronic diseases.

Compared with Zurich, the Alps loom startlingly close and high behind the medieval spires of the Swiss capital, Bern. The city is home to the Swiss National Science Foundation, mandated by the federal government to support and fund basic science across all academic disciplines.

According to the funder’s director, Angelika Kalt, “bright minds are the wealth of Switzerland”. Reflecting on the prospects of an exit from Horizon 2020, she says: “If conditions for doing research deteriorate in the country, that will lead to a less investment-friendly climate. There are lots of start-ups and enterprises that settle in Switzerland around universities, especially the two federal ones.”

ETH Zurich and the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne are the two universities administered by the federal government, with the latter standing at 31st in the THE World University Rankings 2015-16. The canton-administered universities of Basel, Zurich, Bern, Geneva and Lausanne are all placed between 101 and 144 – an impressive tally for such a small nation.

Kalt points out that an exit from Horizon 2020 would mean that holders of ERC grants could no longer bring their funding with them to work in Swiss universities. “We would probably observe that researchers would like to work in more open countries, where they have access to all kinds of mobility and transfer grant possibilities. That may even lead to a brain drain of Swiss people because they may also prefer to work in more openness. In the end, that may have a real impact on Switzerland,” she says.

In the event of an exit from Horizon 2020, her foundation would have “to come up with replacement schemes for the ERC instruments”, says Kalt. It did this when ERC participation was temporarily blocked in 2014, setting up a national grant awards scheme assessed by international panels. But that experience confirms that such a national scheme is “going to be an evaluation…on a much smaller basis than it would be at a European level”, says Kalt, adding that “the reputation of such a grant is not the same as a real ERC grant”.

Switzerland even has a specific government-funded organisation, known as Euresearch, dedicated to “providing targeted information, hands-on advice and transnational partnering related to European research and innovation programmes”. Its Bern office is headed by Maddalena Tognola, who also oversees the grants office at the University of Bern. She says that uncertainty over future ERC participation is already having an impact on Swiss recruitment of foreign researchers. “We notice that people who want to move to Switzerland ask: ‘Are we eligible for ERC grants, and how does it look in the future?’”

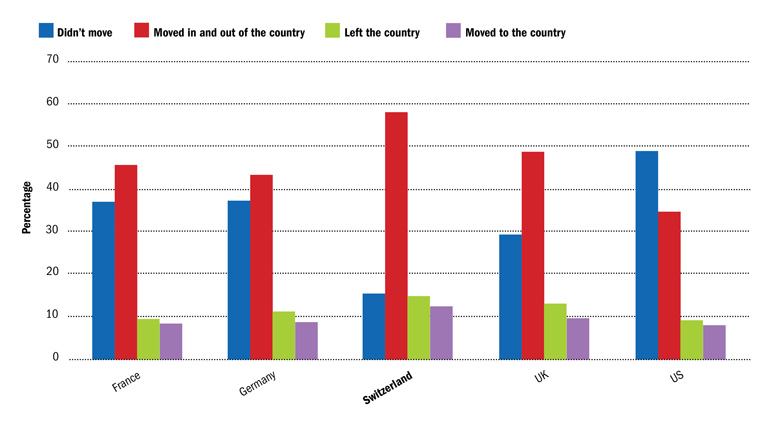

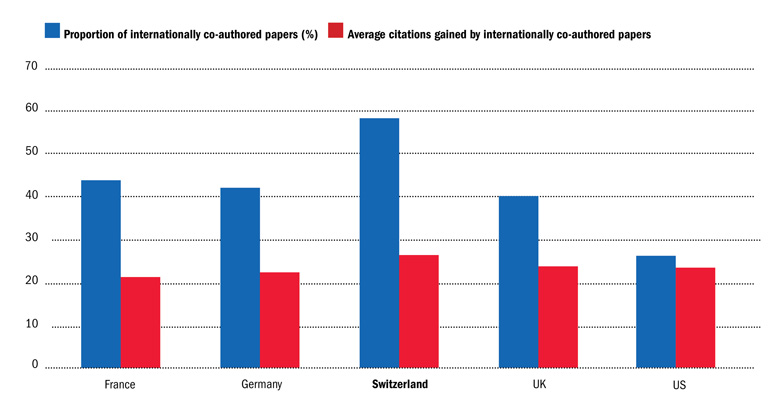

Researcher mobility since 1996

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal

Data gathered for THE by Elsevier (see 'Swiss research performance 2001-15' graphs, below) show that since first becoming associated to EU research programmes in 2004, Swiss researchers have increased their lead on their counterparts from the UK, the US and Germany in terms of the citation impact of their research (see ‘Citation impact of Switzerland’s researchers since 1996’ and ‘Researcher mobility since 1996’ graphs, above). The data also show that Switzerland has more researchers moving in and out of it than those rival nations, and that it gains a high level of citation impact from those researchers. International mobility and collaboration, it seems, is key to the success of Swiss universities.

If Switzerland is to reach a compromise with the EU over free movement, the stance of the anti-immigration SVP will be crucial – not least because the party has two seats on Switzerland’s seven-member federal council: the collective head of state and also the Cabinet. Can SVP politicians be convinced of the importance of Swiss participation in EU research?

The auguries do not appear to be favourable. Any group of Swiss citizens can propose a change to the federal constitution via a referendum if they secure 100,000 signatories to a petition, and the SVP has proved effective in using such tactics. In a more recent campaign to introduce deportation for foreigners convicted of minor crimes (which Swiss voters rejected), SVP posters depicted a white sheep kicking a black sheep off a Swiss flag.

Fathi Derder is a member of Switzerland’s parliament for the liberal Free Democratic Party and a member of parliament’s Science, Education and Culture Committee. His view is that Switzerland needs to be “fully associated” to Horizon 2020. But he adds that, in political terms, there is “a great problem with research. The population doesn’t really realise what it means. If you cut the budget in research, no one will feel it tomorrow. They will feel it in 10 or 20 years.” Hence, “populist parties” such as the SVP “are not really going to fight for research. That’s a big danger.”

Kalt says of the SVP: “The party line is certainly that Horizon 2020 is not really necessary. But there are voices in the SVP who think that openness would be good. So I think there is more work to be invested specifically for that party, but it’s extremely difficult.”

Thomas Aeschi, an SVP politician regarded as being among the party’s new leadership generation, says: “We will not let the European Union blackmail Switzerland with the Horizon 2020 programme. According to the public vote of February 2014, the introduction of immigration quotas and the restriction of free movement of labour to Switzerland has number one priority. If the European Union threatens to lock out Switzerland from the Horizon 2020 programme, Switzerland’s excellent universities need to partner with leading universities in the UK, the US and Asia (eg, Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai or Tokyo).”

Felix Müri is an SVP member of parliament and one of two presidents of the legislature’s Science, Education and Culture Committee.

Swiss research performance 2001-15: research quality

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal

“Having full access is certainly worthwhile, but not at any political price,” Müri says of Horizon 2020.

He claims that “businesses are still the main driving force behind Switzerland’s research and development activities” and that the reputation of Swiss research would “not be harmed” by a Horizon 2020 exit “because we are in a strong position due to our quality and our international network”.

Müri adds: “If anything, the image of the EU research programmes would be more likely to suffer because our exclusion would highlight yet again how politically motivated these programmes are and how little regard they have for the global freedom to conduct research.”

Asked if ensuring continued Swiss access to Horizon 2020 necessarily means ratifying the free movement deal with Croatia, he replies that “countries like Israel, for example, are fully associated members of Horizon 2020 even though they have no free movement of people agreement with the EU; nor are they candidates for EU membership. Given the necessary political will and assured negotiating skills, alternative solutions are possible.”

Do SVP parliamentarians see the future success of Swiss universities as an important factor to protect in talks with the EU?

“This is one of the many factors that need to be taken into account in our negotiations,” says Müri. “The absolute priority for the SVP, however, is to maintain Switzerland’s political and institutional independence, as well as its sovereign control of immigration policy, as required by our federal constitution.” The Swiss presidency, which is held on a rotating basis by federal council members, is currently held by the Free Democratic Party’s Johann Schneider-Ammann, Cabinet member for the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research. He will renew talks with European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker this month to seek a resolution of the free movement stand-off. In May, Schneider-Ammann said of Horizon 2020 that “we can’t afford not to play in the Champions League any more and not be fully involved”.

There is widespread agreement among senior figures in universities and research that their sectors were too quiet before the immigration referendum. But they have learned that lesson and are now willing to speak out on political issues – notably free movement – that directly affect their potential for future success. This, Hengartner says, “bodes well for the mother of all public votes that we’ll have regarding the Swiss-EU relationship” in the potential second referendum.

Kalt says that the lesson of recent events is that “completely independent of any political situation, the funding agencies [and] universities…should take more care to get into contact with the people who are not concerned about science at all, to make them understand that progress and wealth and well-being are to a very large extent dependent on the results of research”.

Swiss research performance 2001-15: international collaboration

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal

So what lessons might universities in the UK, and across Europe, learn from Switzerland’s experiences?

Kalt says that “for both countries, it is very important to maintain at least a minimum of access to these European instruments. Because, [whether] you’re big or small, in research what counts is to have international networks, to have access to international infrastructure, to be able to publish across borders and to have the reputation [conferred by] a high-level European grant. No national competition can come up to that, not even in the UK, I think.”

In Hengartner’s view, “the message to UK universities is [that] it will be challenging for you to negotiate an active participation in [EU research] programmes without also compromising significantly on movement of people.”

The suggestion is that the EU might also demand that the UK continue to subscribe to free movement if it wants to join EU research programmes. “I am fairly confident that the UK is not going to get a separate agreement on Horizon 2020,” Hengartner says. “Horizon 2020 will simply be part of the general discussions [on future relations] that the UK and the EU will have.” Thus universities “cannot hope for a rapid decision” on association to Horizon 2020 or the successor Framework Programme Nine, he adds.

So, as the UK starts to consider its future relationship with the EU, its government and citizens will have to decide – just as the Swiss will in any second referendum – whether worries about immigration are important enough to justify the economic and scientific sacrifices that ending free movement will involve. The implications for universities, given the benefits that they gain from free movement for students and researchers as well as a general climate of openness, are huge.

Whether universities are influential enough to sway the public on these issues is another matter. The Free Democratic Party’s Derder says that his regretful view is that Swiss universities are broadly perceived by the public as “kind of an elite” and that “the more they talk, the less people listen to them”.

On immigration in Switzerland, Guzzella acknowledges that the “dramatic and rapid increase of population is not without consequences. Not everybody wins in globalisation.” However, he adds of those who voted for restrictions: “I don’t think all of them…really wanted migration to be limited, but they wanted to send a signal to the government.”

Guzzella stresses that “science has no borders. There is not a physics in Italy and a physics in Germany. There is only one physics. And it is very obvious that as soon as you start limiting the flow of ideas – and ideas very often…travel with people – you will weaken the system.”

Hence, “if Europe wants to [compete] in digitalisation, the internet of things, Industry 4.0…if Europe wants to catch up with the US and technology developments in Asia, there is no way we should start building barriers and boundaries and fences among ourselves”.

后记

Print headline: A mountain of worries