A strong science base has offered little protection against the coronavirus pandemic, according to one of the discoverers of Ebola, who stressed that excellent research only helps countries steer through a crisis if there are already good channels of communication between politicians and scientists.

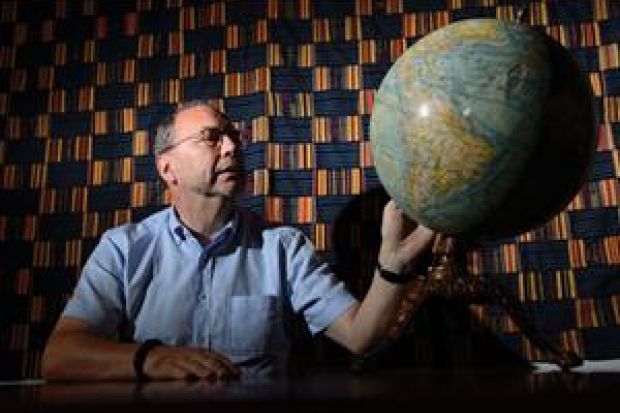

Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, observed that the US and the UK had conspicuously fallen short, while poorer nations such as Vietnam and Senegal had mounted much more effective responses.

“Having strong scientists and strong research is not a guarantee that it will influence or be translated or adopted by politicians. Absolutely not,” he told delegates at the European Research and Innovation Days, an annual EU conference held online this year, on 24 September.

It was crucial that scientists and policymakers know each other before crisis hits, Professor Piot argued, as they must understand how to communicate “when the sun shines”, not just in desperate moments.

He made the comments during a discussion in which scientific advisers from the EU, US and UK tried to draw lessons from the pandemic so far.

Plenty of criticism was reserved for politicians – but the scientific community was found to be at fault too.

Politicians had tried to blame scientists for their own failures, Professor Piot said, and foolishly attempted to explain “very complex scientific things” to the public.

Later on in the debate, he singled out UK prime minister Boris Johnson for “giving a lecture on [virus] reproduction rates – I mean, it’s close to being ridiculous. Frankly, it’s not even very useful.”

But there was also concern that scientists also may have overstepped their mark in the debate over how to respond to the virus.

“Scientists advise, and politicians or policymakers decide,” Professor Piot said. “Not all scientists understand that.”

“Policy is most of the time about trade-offs,” he added. “That, in science, we don’t always like – we don’t like these compromises.”

This was echoed by Pearl Dykstra, one of the European Commission’s chief scientific advisers.

“Researchers and scientific advisers should also recognise that politicians sometimes have to make difficult decisions and they may choose not to follow the policy advice, but if they do so, they should make that clear and give their reasons,” she said.

It is also crucial that scientists and politicians explain their uncertainties to the public, the advisers agreed.

The public was too often taught in school that scientific findings are “chiselled in granite”, meaning that when crisis struck, it was hard to explain how and why scientists were unsure, said Sir Paul Nurse, director of the Francis Crick Institute in London.

“Politicians can be tempted to simplify,” said Sir Paul, who is also a chief scientific adviser to the EU. Too often during the pandemic, they had communicated in “tabloid-type headlines”.

“It’s not enough for politicians to say they’re following the science,” said Professor Dykstra. “They need to understand the uncertainty in the science, and its relation to the recommended measures, and to communicate that to the public well.”