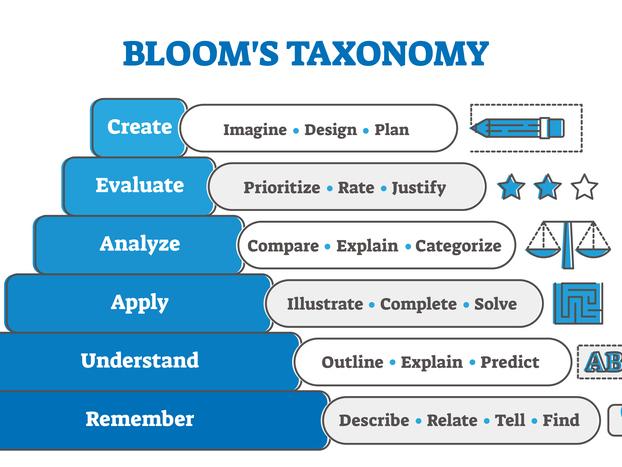

Don’t forget Bloom’s Taxonomy’s ‘remembering’ level

Bloom’s Taxonomy, a powerful and empowering tool for educators, is pivotal in setting cognitive learning outcomes at various levels. The original version of this taxonomy categorises learning objectives into six progressively increasing levels of thinking: remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating and creating. Remembering, positioned at the base of the taxonomy as the lowest-order cognitive level, is a crucial skill for lecturers to activate in students and for students to cultivate in themselves.

Remembering is a cognitive activity that involves storing and retrieving information in the brain. Sensory memories are created when a learner receives information through one of the sensory receptors. These memories are fleeting and may last only a few seconds. The learner must attempt to process sensory memories so that they become a part of the working memory, which educational theorists refer to as schemata, which organises information. Learners interact with working memory schemata while the topic is being taught. However, these memories can be encoded and aligned with prior knowledge to form long-term memories. Although long-term memories can be retrieved years later, when required, they can also be readily retrieved and used as working memories soon after the teaching and learning interaction has ended.

In this information-accessible era, the importance of memorising details may be underestimated. However, in a teaching and learning setting, remembering (storing and retrieving information from schemata) is a vital component of learning big-picture concepts. Moreover, while at the core are easily accessible facts detailing descriptions, processes and relationships, fluent learning requires students to be able to automatically retrieve this basic information as they seek to attend more cognitive efforts on higher-order thinking.

- Resource collection: Teaching strategies to enhance learning

- How to teach critical thinking to beginners

- Four ways active learning can transform learning experiences

Students will naturally remember only 10 per cent of what they read, 20 per cent of what they hear and 30 per cent of what they view, according to Edgar Dale’s Cone of Learning. Reading, hearing and viewing represent most of the modes of communication used in the tertiary classroom. Therefore, implementing strategies that promote a greater level of remembering should be a priority for educators. Here are some pointers that lecturers may consider to increase students’ ability to remember information:

- Activate the sensory memory by complementing verbal lectures with attention-grabbing sensory stimuli such as music, tactile manipulatives and visuals (videos and graphic organisers). Be careful to make a clear connection between the stimuli and the big idea, otherwise, some students may remember the stimuli but not the big idea

- No one will be able to remember everything that they experience in the classroom. Help students identify the most important ideas that they need to remember to grasp the big-picture concept

- Make clear distinctions between the main ideas that students should remember and other supplemental details, such as examples, descriptions and statistics

- Present the key ideas to be remembered in multiple ways: verbally, in written text and through graphic displays and demonstrations. Since all students learn differently, stimulate as many sensory elements as possible to encourage memory storage

- Use repetition to reinforce details that should be remembered as many times as possible. Some students will not even hear or see the information the first time it is presented

- Provide students with prompts to encourage peer-to-peer discussions and opportunities to present their learning

- Pause for 20 to 30 seconds after presenting a major concept to allow students to process the information and develop working memories

- Limit the number of things students need to remember to understand the big-picture idea to two or three per two-hour session

- Point students to the source of the information so that they may create personal opportunities outside of class to experience and commit it to memory

- Connect the new thing that students need to remember with prerequisite (old) or experiential knowledge they already possess.

Remembering key elements of big ideas is critical to consolidating students’ understanding and engaging in higher-order thinking. Although the apex of learning is creating new knowledge and solutions, at its foundation is remembering related principles and processes, and educators play a crucial role in guiding students to do this.

Adeola Matthew is a recruitment officer at the University of the West Indies Five Islands Campus.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.