RIP assessment?

You may also like

The growth of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has challenged educators to think differently about teaching, learning and assessment. Universities (and the media) concentrated initially on the perceived risks associated with GenAI, and the extent to which it could undermine assessment practices, processes and policy. Yet, assessment in higher education has long been susceptible to issues around authenticity and validity. In April 2022, for example, some seven months before OpenAI released ChatGPT, the UK government criminalised essay mills for fear of increased contract cheating by students.

Instead, it is more useful to consider the advent of GenAI as an opportunity to review our assessment practices and to reconsider what knowledge, understanding and skills we most value and wish to reward.

To address this significant challenge, the University of Bath is taking a leading role in responding to GenAI, exploring how our assessments can best prepare our graduates for their futures rather than our pasts. In a world where artificial and human intelligence coexist, we are asking: how can we ensure that our students effectively critique their own use of AI in assessments (where permitted) and how can our teaching help develop the human attributes, such as creativity, self-awareness and critical thinking, that will be so needed in the future workplace?

- AI did not disturb assessment – it just made our mistakes visible

- Spotlight guide: Bringing GenAI into the university classroom

- Resource collection: AI and assessment in higher education

We cannot easily untangle a world where GenAI is not just everywhere but is inside everything but we can ensure that our students develop holistically, excel in critical thinking and gain the confidence and skills to use GenAI effectively to advance their ideas and learning.

In other words, we can attempt to make human learning visible in our assessments.

A plan to focus assessment on human strengths

We are driving ahead with plans to focus on what humans do best, either on their own or using GenAI as a tool. The key point for us is ensuring that where GenAI is permitted in our assessments, students also advance their own learning, voice, critical thinking and originality of ideas, rather than to replace them.

Our plan has four steps:

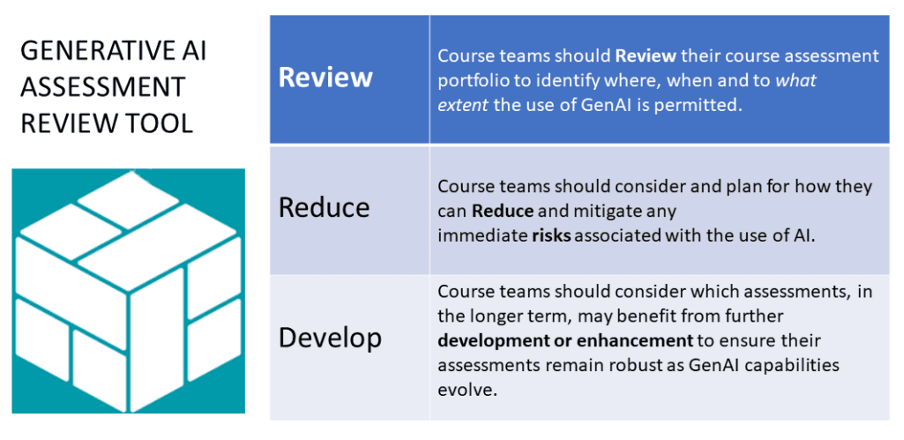

Step 1: review, reduce and develop

Academic staff are reviewing all our assessments against a threefold categorisation model of permitted GenAI usage that we have developed (based on one developed by University College London). From September 2024, all assessments will clearly signal to students the extent to which GenAI is permitted in each assignment. Specifically, staff have been asked to:

Reviewing all our assessments is no mean feat. We recognise the impact that this has on time-poor academic staff, and we are running workshops, developing communities of practice and developing case studies and centralised guidance to support them.

Step 2: research

We have identified that graduates will need a transparent understanding of how they are learning in terms of the critical choices they make, the information or knowledge they engage with, and where machine learning ends and theirs begins. Equally, staff need clarity and support to rethink the assessment of these skills in ways that are reliable and robust.

We do not have the answers to all this yet. Instead, the university has secured Quality Assurance Agency funding for a joint project with Stellenbosch University in South Africa to make critical thinking more visible and explore the intersection between human and GenAI learning.

Step 3: delivering authentic assessment

We have completed an institution-wide curriculum transformation project, intended to promote forms of assessment that are authentic, applied or real-world-based. This has given us a strong foundation to place human learning and human endeavour at the heart of our assessment design. The emergence of GenAI does not threaten or undermine this trajectory. Rather, it reinforces the need for assessment that is grounded in reality and human experiences and furthers our strategic aims.

Step 4: develop examples

We have awarded internal teaching innovation funding to James Fern (from the department for health) to undertake a project to engage with national and international employers, in-house world-leading AI researchers and our own students. The aim is to better understand their perceptions and expectations of GenAI, so our response to GenAI is grounded in what people want from the tool rather than being driven by technological advances themselves.

We are also exploring creative approaches to harnessing GenAI as a tool to reinforce and support (rather than replace) human learning. For instance, Harish Tayar Madabushi (department of computer science) is developing an AI tool that can draw on his video recordings to create reusable and personalised learning resources; and Kim Watts and Carl-Philip Ahlbom (from the School of Management) are exploring the potential of training a model on marked assessments to develop a personalised formative feedback chatbot for students.

Finding GenAI’s Achilles’ heel

While the widespread impact of GenAI within education should not be underestimated, the very strength of GenAI is also its Achilles’ heel. Anyone can access, garner and generate data rapidly but human beings have never had a greater need for scrutiny and evaluation of this output. HE has always promoted critical thinking and the rigorous investigation and examination of the production of knowledge. Now, more than ever, we need graduates who can critically engage with their learning, and we need assessments that will capture and evidence this. The only way to do this effectively is to put people at the start, middle and end of our assessment journey.

Abby Osborne is assessment and feedback development lead and Christopher Bonfield is director of the Centre for Learning and Teaching, both at the University of Bath. They lead the institution’s response to GenAI in Education.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.