What does it mean for students to be AI-ready?

The widespread availability of AI tools drives a persistent question about what they mean for education. A lot of this conversation over the past two years has focused on writing and computer programming. How do we assess these subjects when students can generate customised, original content using tools available to anyone with an internet connection?

This initial fear is a great entry point into discussion about the AI-augmented future of education. Georgia Tech’s new course series, ChatGPT for Educators, and my book, A Teacher’s Guide to Conversational AI, both address assessment design in the age of AI because that task drives the most urgent changes educators must make. However, this is merely a gateway into what it means to prepare our students for the AI-augmented workplace they will enter upon graduation.

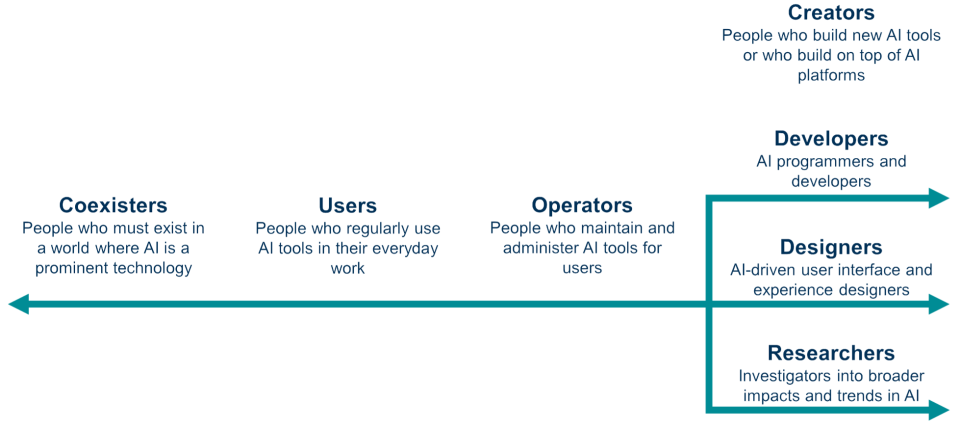

Like automobiles, computers and the internet, AI has a revolutionary relevance that comes from its capacity to drive demand for skills across a robust spectrum. To categorise how we ought to begin to frame teaching AI skills to our students, I assembled a spectrum of people’s responses to artificial intelligence (see below).

Far too often, I find the conversation around AI literacy is restricted to the end points of this spectrum. On the far left are coexisters, where AI will be a persistent force in our students’ lives, and we must teach them – as best as we can, given how many unknowns remain – how to exist in the world they are entering. Too often, traditional education prepares students for the worlds into which their schools and universities emerged, not the world they exist in now. Part of AI literacy will be ensuring students are ready to interrogate the content they consume; coexisting with AI will mean understanding how it influences what we see.

Similarly, on the far right, we find creators, developers, designers and researchers, people who will see AI as likely to be one of the most significant growth sectors in the coming years. Organisations will be desperate for workers who can build AI tools in order to remain competitive. Fears are rising that the growth of AI will dampen some of these career prospects, but we also know that across human history, technology has created significantly more jobs than it has taken. It is naive to assume that will always remain the case, but in the foreseeable future, there will be enormous work for people with the necessary skills to bring about some of what we see as possible.

- Higher education needs a united approach to AI

- Enhance GenAI collaboration for future-proof research support

- How to assess and enhance students’ AI literacy

But in my experience, these end points are too often treated as the only directions to prepare students for the impact of AI. We either prepare students for a world in which AI is an external phenomenon that happens to them, like the weather; or we are prepare them for a small set of future jobs. Not everyone wants to be a computer scientist, a software engineer or a machine learning developer, which is perfectly fine.

In between those extremes is an enormous range of AI skills that are not relevant to everyone but apply to far more people than the developers of future AI tools. For all the panic about student use of AI in essay generation, there is enormous potential to teach students to use AI to support organising and communicating their thoughts. Critically, these new tools will allow students to contribute more of their insights – but only if we teach them appropriate usage.

Similarly, there will be enormous roles in the future for those with AI literacy to support others’ usage of AI technologies. In my day job, I run Georgia Tech’s online master’s programme in computer science (CS), and one common archetype of students we see are those with no formal CS education but who got into software development or programming because their workplace had a small project that required technical ability. These students picked up these skills independently and, over time, became their organisation’s go-to developer.

AI will see a similar arc. Some individuals will develop, mainly through self-study and experimentation, an aptitude with these tools that will pay enormous dividends in how they can support the teams around them. These operators will have a multiplicative role in their organisations, even as they need not develop new AI technologies; they will just need to understand how to select the right AI tool for the appropriate problem.

We owe it to our students to prepare them for this full range of AI skills, not merely the end points. The best way to fulfil this responsibility is to acknowledge and examine this new category of tools. More and more tools that students use daily – word processors, email, presentation software, development environments and more – have AI-based features. Practising with these tools is a valuable exercise for students, so we should not prohibit that behaviour. But at the same time, we do not have to just shrug our shoulders and accept however much AI assistance students feel like using.

Instead, these interactions should be the foundations of conversations and discussions of these AI tools: how did using an AI tool affect that result? How does it differ from what the student would do alone, both in terms of efficiency and learning outcomes? How does it change how the recipient interprets the student’s work?

These conversations are crucial to understanding how AI assistance will be perceived and how it will affect students’ understanding of the content, and they also serve as a powerful gateway into discussing the ethics and morality of using AI tools as a whole.

David Joyner is executive director of online education & OMSCS in the College of Computing, principal research associate and inaugural holder of the Zvi Galil PEACE (pervasive equitable access to computing education) chair at Georgia Tech.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.