Australian educators are mystified to see master’s enrolments stagnating at a time when labour market evolution and changing career patterns are supposedly fuelling a lifelong learning boom.

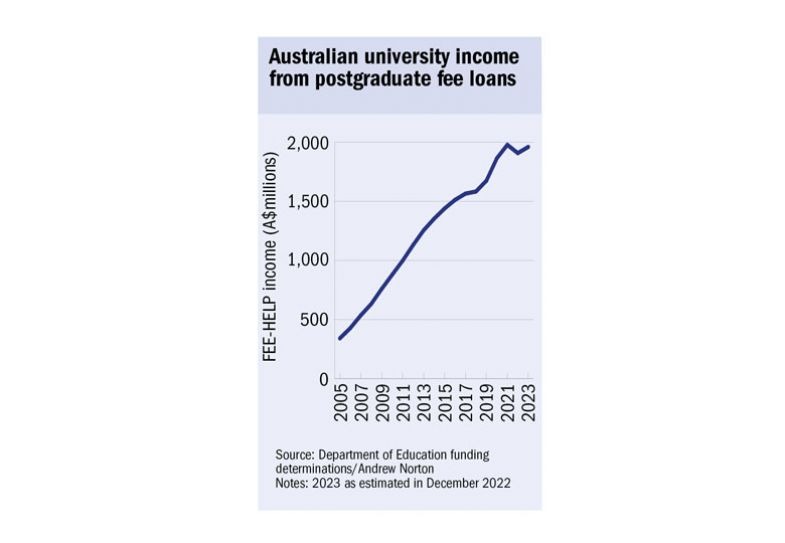

University annual reports show that their income from Fee-Help, the loan scheme covering postgraduate course fees, has fallen sharply. Of the 32 institutions that had published their 2022 financial accounts by mid-June, 24 reported slumps in Fee-Help earnings, with overall declines totalling A$89 million (£48 million), or 9 per cent.

Griffith University vice-chancellor Carolyn Evans said Australia’s market for full-fee postgraduates had been “remarkably static”. Australian National University policy analyst Andrew Norton said domestic enrolments in taught postgraduate courses had barely changed between 2014 and 2019, although there had been an uptick early in the pandemic.

Education department data showed that annual growth in the government’s Fee-Help outlays had fallen from about 25 per cent in the mid-2000s to around 5 per cent in recent years, and declined in 2022. For universities, Professor Norton said, there was “no easy money” in domestic master’s courses. “This market is clearly tough.”

He observed before the pandemic that tertiary education participation was “flat or trending down” among people with established careers. “Everyone keeps saying we have to retrain multiple times…and none of the educational data was supporting that conclusion. There’s something going on which is quite inconsistent with the major narrative around the need for education and training,” he said.

One possibility was that experience was trumping credentials amid “declining turnover” in the workforce. “Maybe employers simply stopped being impressed to some degree by extra qualifications. It’s something we really don’t know enough about.”

Higher education consultant Justin Bokor said employers still valued bachelor’s degrees. “But for postgrad, there are many more options [with] probably a lot better return on investment,” he said. “Twenty-five years ago, if you wanted to get ahead in corporate life, you’d do an MBA. Now there are short courses and myriad different providers.”

This might disadvantage universities but not necessarily anybody else, Mr Bokor said. Employers no longer needed to lose “highly productive employees” for many months, and workers no longer needed to relinquish pay or “flog” themselves as part-time students. “Just do a six-week course, and you get the same outcome.”

But Andrew Parfitt, vice-chancellor of the University of Technology Sydney, said the “largely flat” postgraduate enrolments of the past decade spelled trouble for a changing economy.

He said cyber developments, for example, warranted continued upskilling. “In a workforce where 40 per cent of young people have undergraduate degrees, what’s the next evolution? We’re not necessarily tooled up for that next stage of formal learning.”

Professor Parfitt said the lack of appetite for master’s study partly reflected the quality of Australia’s undergraduate education. “For the vast majority of professions, you don’t need a postgraduate qualification as a pathway to entry. Master’s degrees have a place if you want advanced level skills or to shift into professionally accredited disciplines [not facilitated by] your undergraduate degree.

“But it just doesn’t seem that the return on quite a sizeable investment is being perceived either by employers or employees.”

He said this problem could be alleviated if universities shifted more of their teaching subsidies into postgraduate courses, but the funding rules – which capped contributions from government-supported students at levels geared towards undergraduate study – made this unaffordable.